In 1970 Marlene Sanders, a legendary woman journalist, and Emmy-award-winning correspondent produced and reported an ABC News feature about the women's liberation movement. Sanders began her career in an entry-level job in 1955 at WNEW-TV in New York, and she worked her way up to become the producer of the show, an almost unprecedented achievement for a woman in television then. After that, Sanders broke barrier after barrier. She was the first woman to cover the Vietnam War on the ground, co-anchor a national nightly news show, and become a vice president in the ABC News division.

Unsurprisingly, Sanders was well-connected in New York's small but thriving women's liberation community. The feature included an interview with Betty Friedan, the author of the 1963 best seller, The Feminine Mystique and one of the founders—along with luminaries like Pauli Murray, Aileen Fernandez, and Shirley Chisholm--of the National Organization for Women, known as NOW .

Although NOW had radical goals, the organization sat firmly in the tradition of American liberalism, seeking to reform the system, not overthrow it, and to do so through politics, legal action, and the occasional peaceful protest. NOW wanted equality, not revolution.

But Sanders also included footage of women who wanted a wholesale re-envisioning of the social order. They were radical feminists like Susan Brownmiller, who Sanders knew from the New York movement and journalism circles, and activists in places like Chapel Hill, North Carolina. There, radical feminists—mostly students, and wives of students--were upending traditional gender roles, parenting, marriage, and sex and laying the groundwork for an academic field called "women's studies."

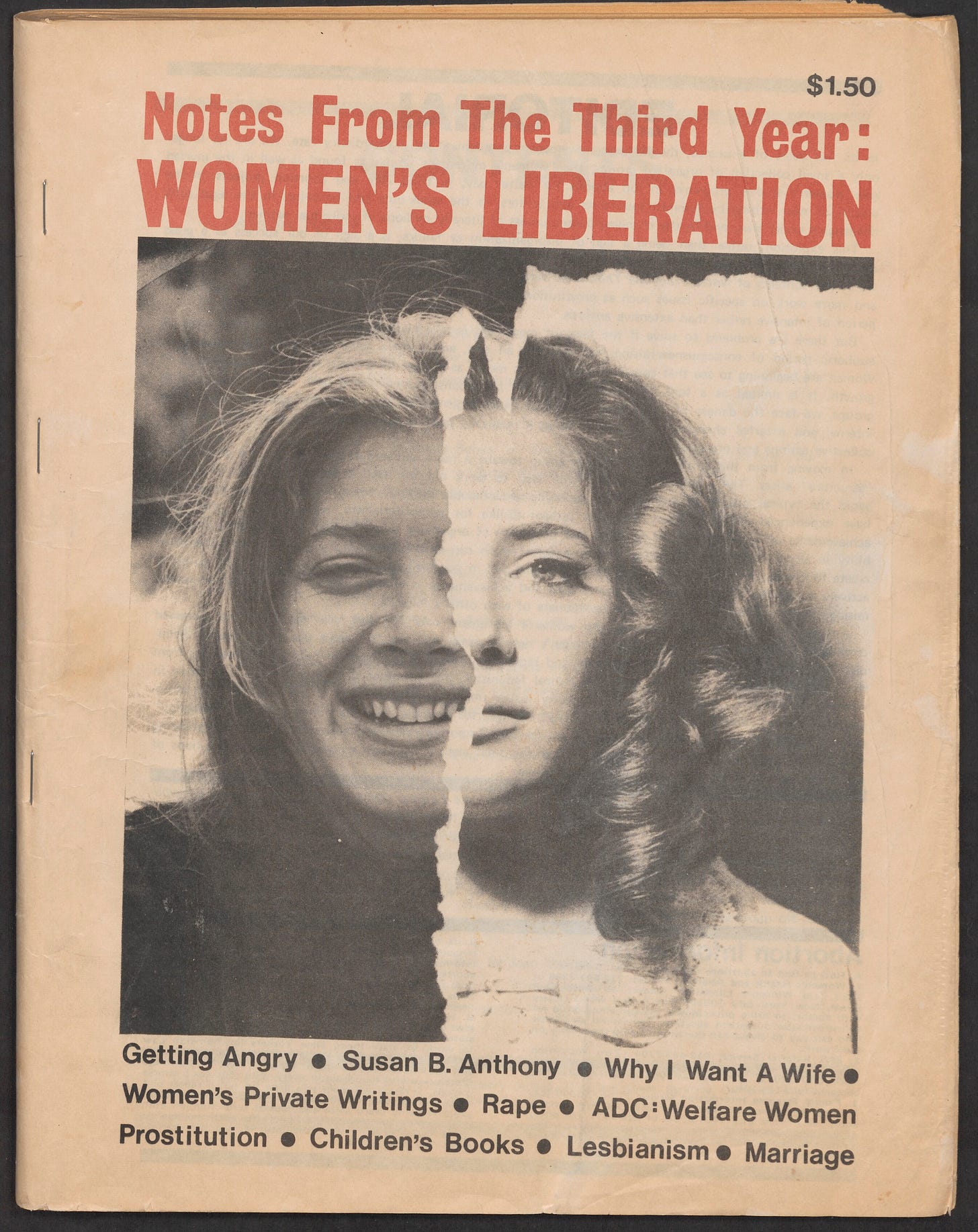

Radical feminist organizations were often short-lived, beginning as conversation or "rap" groups among women whose politics and sense of grievance had been formed in the Black civil rights and anti-war movements. Those movements had taught them the pervasiveness of racism in American society, so they invented a word that expressed the potential for women's class consciousness: sexism. And they adapted another name from the Old Left for their process: they called it consciousness-raising.

Revolutionary feminists often came from a Marxist background. Like many on the New Left, some were the children of communists, so-called "Red Diaper” babies. Others were neighborhood organizers, college graduates who had ended up at home with children or in jobs where they couldn't be promoted any higher than secretary--or wife. They wanted egalitarian relationships with men, but that was only a starting place--if an important one for the heterosexually inclined.

Unlike NOW, they organized speak outs, demonstrations, and sit-ins, making demands that liberal professional women often saw as too confrontational and alienating to men: universal childcare, an end to "mindless boobie-girl syndrome" promoted by capitalist enterprises like the Miss America Pageant, Playboy magazine, and yes—the housewives' friend, the Ladies Home Journal.

These groups named themselves after radical women like Emma Goldman, angry Greek goddesses and demi-goddesses, names that catapulted radical feminists onto the front lines of a social revolution and a new society. New York Radical Feminists broke into "brigades" anchored in neighborhoods; another group adopted the name Redstockings. The Jane Collective came together in Chicago to steer women to safe, affordable abortion providers. Eventually, they taught each other to perform the procedure themselves. In Washington, D.C., one of many lesbian separatist groups called themselves The Furies: heterosexuality, along with private property, they argued, was an impediment to a women's revolution.

Of course, only a fraction of the stories about radical feminism have been told: one of those untold stories may even be in your city or town. And a story that has never been told until now is of the revolutionary feminist community in Seattle. In this city, white women and women of color worked successfully in coalition with each other and with neighborhood organizers. Activists made it a priority to support unions, and selective use of the political process resulted in the first successful ballot referendum to decriminalize abortion.

This is why I wanted to talk to Barbara Winslow, Professor Emerita of Women's and Gender Studies at Brooklyn College. Winslow's new book, Revolutionary Feminists: The Women's Liberation Movement in Seattle (Duke University Press, 2023) tells the story of feminists who were not only at the forefront of a women's revolution but who saw their anti-racist, anti-imperialist, class-conscious organizing as the natural outcome of that city's radical past. They were Marxists, Maoists, Trotskyists, socialists, Black Panthers, farm workers organizers, and members of SDS—but together, they imagined a non-sectarian feminist revolution in a city they only semi-facetiously thought of as "The Soviet of Washington." And as early as 1965—earlier, in fact, than the founding of many more famous women's liberation movements—Seattle women began to find each other and organize.

And Barbara Winslow was one of them.

Program Notes:

Claire and Barbara talk about Seattle’s long tradition of interracial activism: you can read more about this in Diana K. Johnson, Seattle in Coalition: Multiracial Alliances, Labor Politics, and Transnational Activism in the Pacific Northwest, 1970–1999 (University of North Carolina Press, 2023.)

Barbara notes the International Workers of the World (IWW), and Seattle’s radical past, as context for the rise of a distinctive feminist movement. Listeners may want to follow up with Philip Foner’s History of the Labor Movement in the United States: Industrial Workers of the World (International Publishing, 1973) and Dana Frank, Purchasing Power: Consumer Organizing, Gender, and the Seattle Labor Movement, 1919–1929 (Cambridge University Press, 1994.)

Barbara mentions feminist leadership of the 1919 Seattle General Strike, a work stoppage when workers ran the city for days.

Barbara points us to Julia Reichart’s 1976 labor history documentary “Union Maids.”

Claire brings up Sarah Evans’s book Personal Politics: The Roots of Women's Liberation in the Civil Rights Movement & the New Left (Random House, 1979.)

Listeners interested in where radical feminism fits in the history of the New Left may wish to consult Van Gosse, Rethinking the New Left: An Interpretative History (Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.)

You can download this podcast here or subscribe for free on Apple iTunes, Spotify, Google Podcasts, or Soundcloud. And if you liked this episode, please join us!

If you liked this episode, you might want to try:

Episode 5: Verdi, Dante, and Dahlia Lithwick: A conversation with Slate's Supreme Court reporter about her new book, "Lady Justice: Women, the Law, and the Battle to Save America"

Episode 17: Abortion On Demand: Feminist journalist Katha Pollitt explains why we should treat ending a pregnancy as normal

Episode 22: Hit Them In The Pocketbook: A conversation with Annelise Orleck about her book, "Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty"

Episode 25: Lavender and Red: A conversation with historian Bettina Aptheker about her book "Communists in Closets: Queering the History, 1930s-1990s"

Share this post