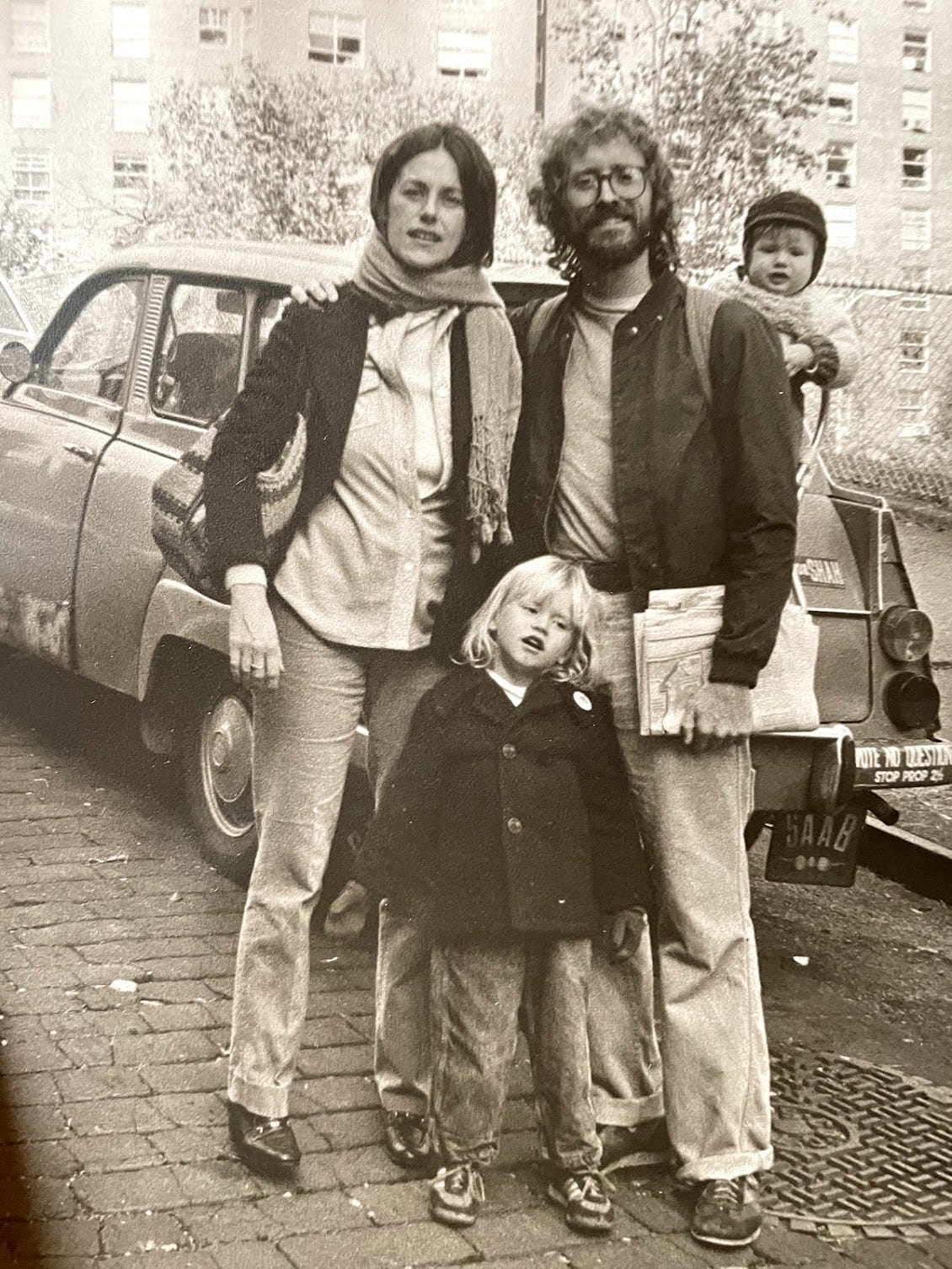

When I was a kid in the 1960s and `70s, I occasionally accompanied my mother to the post office in the Philadelphia suburb where we lived. While Mom waited in line, I would slide over to a corner of the bulletin board next to the service windows that housed the FBI’s Most Wanted posters. And there they were—Angela Davis, a Black philosophy professor from the University of California, on the run as an accessory to a murder committed in a courthouse during a hearing for Soledad Brother George Jackson, as well as white women in the Weather Underground—Bernardine Dohrn, Kathy Boudin, Judith Clarke, and Cathy Wilkerson.

In different ways, all these women were grown up versions of me. They were children of privilege--they were middle-class, sometimes educated in private schools, alumnae of elite colleges, holders of advanced degrees from prestigious schools—who had turned their backs on “the establishment” to try to end the war by fighting their own government. They offered an example of empowered womanhood at a moment when feminism had not yet reached into my life.

I loved them.

Of course, I didn’t know them either. I just felt like I did—Wilkerson had gone to my parents’ college, Swarthmore, and Boudin was a graduate of Bryn Mawr, a campus I passed every day. Nor was I old enough to absorb the ramifications of how they had chosen to struggle against the twin injustices of racism and imperialism. But I imagined them as the warriors against an unjust war in Vietnam and police violence: other people were talking or organizing non-violent protests, but these women were doing something about it.

Many years later, after I became a historian, I came to know Boudin a little bit, as well as her son Chesa, and it was only then that I fully understood both the principles they had stood up for, and the residual pain that reverberated from the violence the Weather Underground had embraced. But I also came to understand how activists like Davis, Boudin, Dohrn and her partner Bill Ayers, Wilkerson, and Clarke had never wavered in their struggle against racism. Instead, they had rechanneled their activism into contemporary struggles: mass incarceration, AIDS, children’s rights, and the liberation of Palestine.

In his podcast “Mother Country Radicals,” Zayd Ayres Dohrn, Bill Ayers and Bernardine Dohrn’s eldest son and a professor in the School of Communication at Northwestern University, tells the Weather Underground’s story—and muses about what the next generation inherited from their parent’s radical politics.

Program Notes:

The news item about the Capitol Bombing on March 1, 1971, was from the March 2 edition of ABC News with Howard K. Smith and Harry Reasoner: you can listen to the whole report and reports of two other Weather Underground bombings here.

The documentary about the movement that Claire references in her introduction is Weather Underground: The Explosive Story of America’s Most Notorious Revolutionaries (Sam Green and Bill Siegal, 2002).

You can hear the complete Declaration of a State of War by the Weather Underground’s Bernardine Dohrn here and read about the work she did after coming up from underground at the Children and Family Justice Center at the Northwestern University School of Law here.

Weather Underground was a splinter group of Students for a Democratic Society. For an introduction to the group’s history, consider Harvey Pekar and Paul Buhle’s Students for a Democratic Society: A Graphic History (Hill & Wang, 2009), or an insider account by Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS (Vintage, 1974).

Weather Underground was part of an international radical movement, as historian Jeremy Varon explains in Bringing the War Home: The Weather Underground, the Red Army Faction, and Revolutionary Violence in the Sixties and Seventies (University of California Press, 2004).

Black Panther Jamal Joseph is now a writer, theater producer and professor at Columbia University. Read more about his work, and its connection to his early activism.

You can learn more about the murder of Panther leader Fred Hampton from Shaka King’s 2021 bio pic, Judas and the Black Messiah, now streaming on Amazon.

For a look back at the police murder of 10 year-old Clifford Glover in Queens, New York, go here.

When the 11th street townhouse blew up on March 6, 1970 it was a big story: Douglas Robinsin of the New York Times covered it here, and for a more recent reflection by Robert Rosen at The Village Voice, go here.

Zayd mentions Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver as a Weather Underground ally: you might want to read Cleaver’s 1969 memoir, Soul on Ice.

For a contemporary account of the 1981 Brinks robbery, go here.

Follow up what you learned in this episode with memoirs by Bill Ayres, Angela Davis, Assata Shakur, and Cathy Wilkerson.

Thai Jones, who worked on “Mother Country Radicals” tells his own family’s story in A Radical Line: From the Labor Movement to the Weather Underground, One Family's Century of Conscience Tthe Free Press, 2004)

You can download this podcast here or subscribe for free on Apple iTunes, Spotify, Google Podcasts, or Soundcloud. Do you use another service? Let me know in the comments, and I will submit it to them!

And if you know someone who would enjoy this podcast, please:

Did you enjoy the show? Then:

Share this post