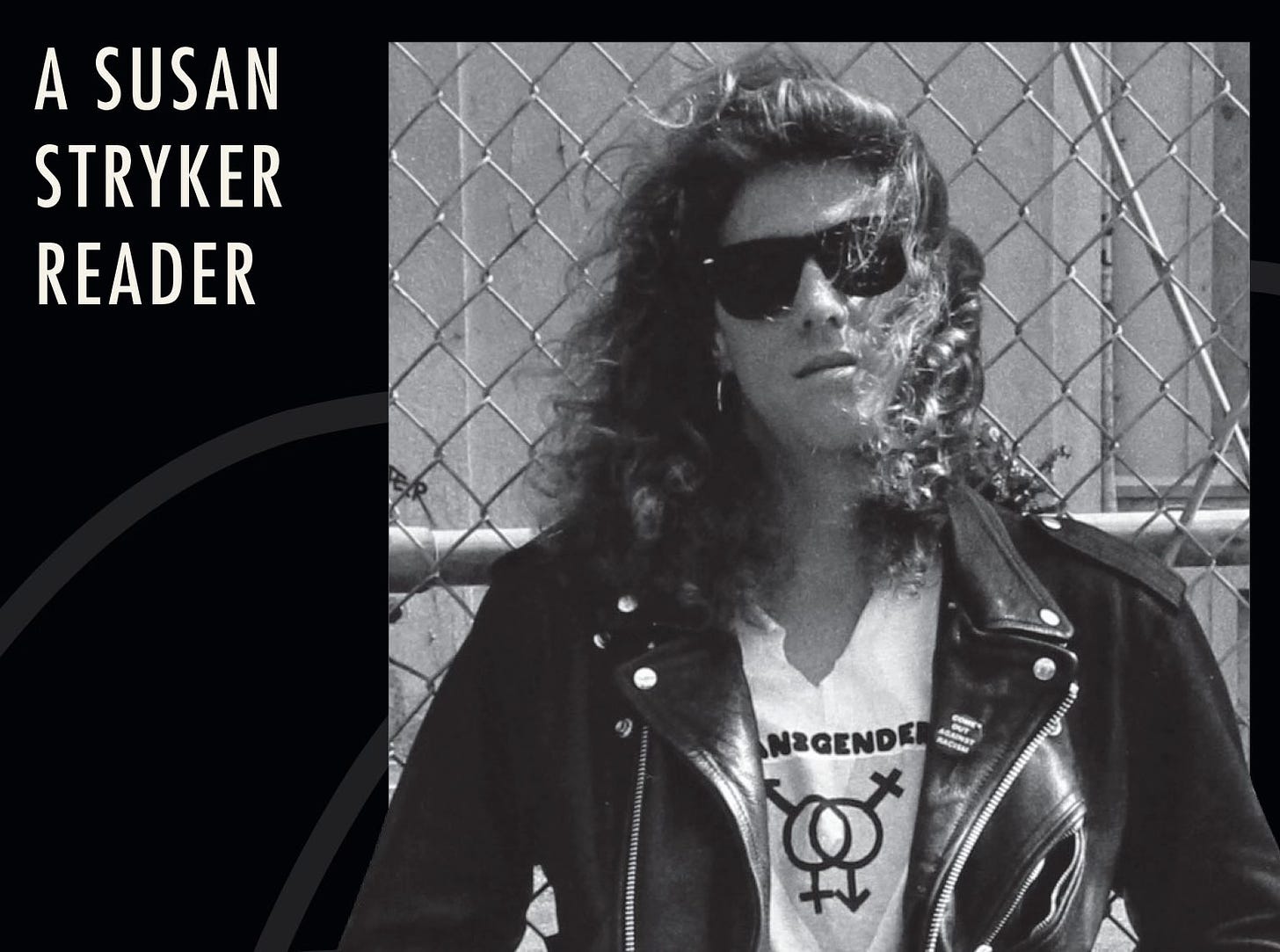

Cover art from Susan Stryker, When Monsters Speak: A Susan Stryker Reader. Photo credit: Loren Rex Cameron.

In the early 1980s, Christine Jorgensen, a performer, celebrity, and the most famous transgender woman in the United States, appeared on Hour Magazine, a television talk show. The host, Gary Collins, asked Christine if she felt more socially accepted since 1952, when she was publicly outed by the New York Daily News following her gender confirmation surgery.

Jorgensen answered with a conditional yes: intellectuals and artists were welcoming to her, but in general, Americans still believed that there were two genders. The exception to that was young people, who were not just accepting, but interested by and engaged with her. Why?

I found Jorgensen’s observations about who she was in the world fascinating for several reasons. First, she was fully engaged with history, correcting Collins when he referred to her as a pioneer, or unique. Jorgensen explained that people had been transitioning, and doctors had been developing techniques to help them do that, for decades before she made her own decision. In addition, Collins kept cajoling Jorgensen into a progress narrative, presuming that Christine—and others like her—must have become gradually more accepted by the public over time as other social minorities had been. But Jorgensen resisted that story as well, pointing to the conservative backlash that had produced Ronald Reagan’s presidency, and linking the new momentum of the anti-abortion movement to potentially more prejudice against women like her.

But the other thing that interested me about Christine Jorgensen’s thinking was that she linked broader understanding of her humanity among the young to a new generation’s curiosity about themselves, and who they might be, and their belief that there were many identities, selves, and bodies available to them, some not yet imagined. If children had toys that could be taken apart and put together in creative new ways, Jorgensen implies, perhaps they could imagine reassembling their own bodies one day.

Christine Jorgensen was no scholar, but she picked up on some themes that would, in ensuing decades, become critical to the history and theory of transgender people. Jack Halberstam, for example, talks about cartoons and children’s play as arenas for grappling with gender, and gender crossing, while historian Jules Gill-Peterson has identified twentieth century pediatrics as a laboratory for changing, and stabilizing, embodied sex.

And notably, for a woman who in many ways sought to naturalize her femininity, Jorgensen briefly runs towards the idea of bodies as constructed things, available for assembly, disassembly, and reassembly, an insight that would be fully developed by historian Susan Stryker in 1994. “The transsexual body is an unnatural body,” Stryker writes in “My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage,” a classic essay in the field. “It is the product of medical science,” Stryker continues; “It is a technological construction. It is flesh torn apart and sewn together again in a shape other than that in which it was born.”

With that essay, even though she had no academic job and no prospect of getting one, Stryker may have inaugurated the field of transgender history. Born and educated in Oklahoma, she had just earned a Ph.D. at the University of California-Berkeley. As Susan made one transition—from graduate student to unemployed historian—she made her second, from one gender to the next. The job market was terrible, and the possibility of being employed as a transwoman was vanishingly small in the early 1990s. So, San Francisco became Stryker’s laboratory. She wrote, she researched, she became a filmmaker, she helped to build an archive, and she learned from other queers on the margins of academia—Patrick Califia, Gayle Rubin. In other words, created a space where transgender history could happen—a door that opened and that younger scholars, artists, and activists now walk through.

And one day, the academy caught up, and came calling. Today, Stryker is Professor Emerita in the Women and Gender Studies Department at the University of Arizona. She has held multiple distinguished fellowships and is the executive editor of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly.

I’ll let Susan tell you the rest, a story in which she becomes one of the most distinguished historians of our generation, and a founding mother in her field. A new collection of Stryker’s essays. edited by McKenzie Wark, When Monsters Speak (Duke, 2024) is evidence of her life’s journey, her intellectual trajectory, and more.

Show notes:

Do you want to learn more about Christine Jorgensen? You can read Christine Jorgensen: A Personal Autobiography, with an introduction by Susan Stryker (Cleis Press, 2000).

In my introduction, I namecheck Jack Halberstam’s The Queer Art of Failure (Duke University Press, 2011) and Jules Gill-Peterson’s Histories of the Transgender Child (University of Minnesota Press, 2018).

You can subscribe to TSQ: A Transgender Studies Quarterly here.

MacKenzie Wark, the editor of Susan’s book and my colleague, is Professor of Culture and Media at Eugene Lang College, The New School. You can take a look at some of her work here.

Susan mentions early work in the history of sexuality by John D’Emilio, Making Trouble (Routledge, 1993); and George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (Basic Books, 2008).

Susan mentions her time as executive director of the San Francisco GLBT Historical Society—where you can go to do your own research.

We discuss anthropologist Gayle Rubin: you can read a selection of her work in Deviations: A Gayle Rubin Reader (Duke University Press, 2011). She also mentions the importance of Patrick Califia, a journalist who wrote for the local queer press and has published multiple books.

You can download this podcast here or subscribe for free on iTunes, Spotify, or Soundcloud. You can also keep up with Political Junkie content and watch me indulge my slightly perverse sense of humor on X, Instagram, Threads, and TikTok.

If you enjoyed this episode, why not try:

Episode 36, The Reality of Desire: A conversation with feminist sex educator, filmmaker and podcast host Tristan Taormino about her new memoir, "A Part of the Heart Can't Be Eaten"

Episode 29, To Sexual Outlaws, With Love: A conversation with the legendary lesbian writer, activist, and community herstorian Joan Nestle about her new collection of essays, "A Sturdy Yes Of A People"

Episode 25, Lavender and Red: A conversation with historian Bettina Aptheker about her book "Communists in Closets: Queering the History, 1930s-1990s"

And here’s a bonus: all new annual subscriptions include a free copy of my book about political media, Political Junkies: From Talk Radio to Twitter, How Alternative Media Hooked Us on Politics and Broke Our Democracy (Basic Books, 2020.)

Share this post