How Conservatives Criminalize Speech

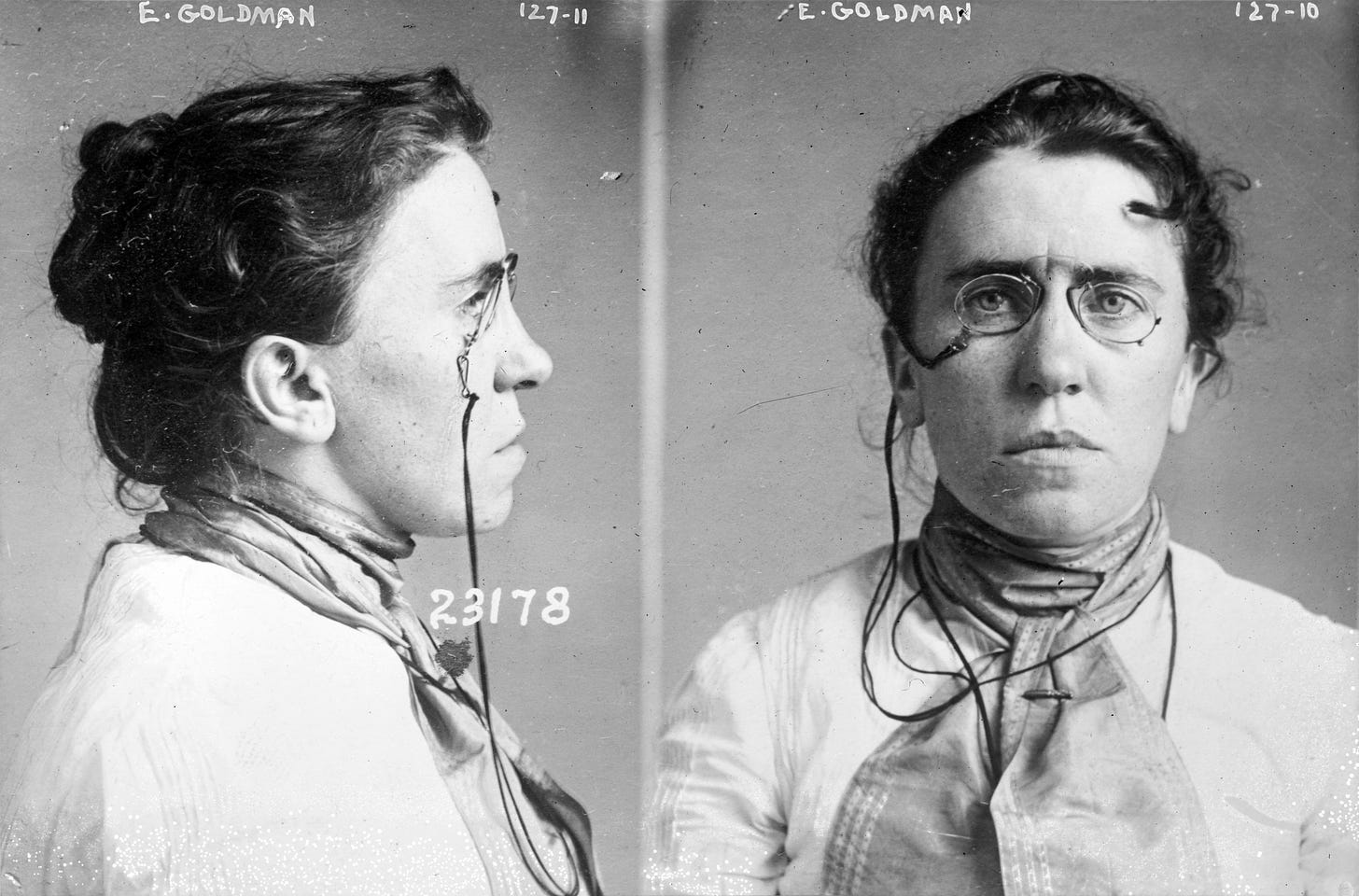

Emma Goldman's 1919 deportation hearing teaches us to pay attention to censorship embedded in other laws

Today’s offering is an edited talk I gave on May 18, 2022, at the American Writers Museum in Chicago. The panel was part of an NEH-funded PEN America series about free speech called “Flashpoints: Free Speech in American History, Culture & Society.” You can read more about the series and events near you here.

My assignment? Reflect on what anarchist feminist Emma Goldman has to teach us about free speech and political dissent. If you know someone who would like this post, please:

Every human being is entitled to hold any opinion that appeals to her or him without making herself or himself liable to persecution. Ever since I have been in this country--and I have lived here practically all my life--it has been dinned into my ears that under the institutions of this alleged Democracy one is entirely free to think and feel as he pleases. What becomes of this sacred guarantee of freedom of thought and conscience when persons are being persecuted and driven out for the very motives and purposes for which the pioneers who built up this country laid down their lives?

Statement by Emma Goldman at her Federal deportation hearing, October 27, 1919

Why was Emma Goldman deported to the Soviet Union on December 21, 1919?

The answer to this question is essential because speech and ideas can be criminalized in many ways and for many purposes. But, most of all, Goldman helps us think about current limitations on speech that are creeping into laws that promote conservative cultural values: the Texas Fetal Heartbeat Act, Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law, and attacks on so-called critical race theory.

In her statement before the court in October, Goldman focused on the effects of the so-called “Anti-Anarchist” law. Officially, that law, which was intended to define all anarchists as potential terrorists, was the Immigration Act of 1903. Congress passed it on March 3 of that year in the wake of President William McKinley’s assassination by self-declared anarchist Leon Czolgosz. The law barred and made deportable for two years after arrival any immigrant opposed to the state (any state, not just the United States); who expressed the willingness to do violence against government officials; or who belonged to an organization that taught such doctrines.

A lesser-known aspect of the 1903 law is its sexual and racial aspects, clauses that mustered nativist and antisemitic politicians and their voters to the cause of suppressing political speech. The law also barred from entry into the United States those who supposedly “imported prostitutes,” an act that was aimed at, but did not name, two categories of people who were not anarchists. The first was Chinese men attempting to bring wives into the United States to establish families and settle permanently. At immigration stations, these women were often categorized out of hand as prostitutes. The 1903 law made it possible not just to deport them but also their future husbands and any marriage broker who might have been involved in the deal.

The second purpose of this clause was to crack down, not just on anarchism as a political philosophy and putative political conspiracy, but to elevate a fake conspiracy. The notion that powerful, unseen forces were trafficking American women as prostitutes was the QAnon of its time. So-called foreigners, often portrayed as Jewish and Asian, were said to drug, entrap, and rape innocent white American girls and then sell them into prostitution.

This fake enterprise was popularly known as “white slavery” and was separately codified as a crime in the 1910 Mann Act. This law targeted interracial relationships almost exclusively, categorizing Black men as rapists and white women as victims. For example, boxer Jack Johnson was arrested on a Mann Act charge in 1920 because he was intimately and consensually involved with a white woman. Not unlike today’s multi-media narratives that prop up QAnon and immigration hysteria on the right, warnings about white slavery and those who suffered from invented sexual violence became the subject of hysterical pamphlets, sensational newspaper, and magazine articles, and by the 1920s, films.

But Goldman’s deportation was also enabled by a second law, written amid American wartime hysteria about infiltrators and the growing revolutionary tide in Russia and Central Europe. In 1918, Congress passed the Dillingham-Hardwick Act, correcting what detractors said was a fatal flaw in the 1903 law: the government’s powers to suppress speech were too limited, and the window for deportation of those like Emma Goldman too small. Adding Communism, labor organizing, and being an “undesirable alien” (this referred to sex crimes or being unable to work) to the list of deportable crimes, the new law included a new definition of anarchism, one that recast speech acts as violence. It also allowed deportation at any time, even if the accused had become a citizen or permanent resident (as Goldman had.)

Today’s efforts to suppress speech are also, coincidentally perhaps, occurring amid a national and global crisis. The recent laws and book bans passed in Florida and Texas, which have now spread to numerous other states, coincide with a global pandemic and, in the United States, attendant anxieties about its effects on children and schools. Similarly, Dillingham-Hardwick was passed amid a global crisis of ideas that drove social conflict. Both Germany and Russia were mired in civil war as Communist governments competed to replace the monarchies that had led them into four years of devastating war. Revolutionaries had murdered heads of state, issuing brazen justifications that defied logic. In July 1918, in the words of Sverdlov, the guy in charge of liquidating counterrevolutionaries in the new Russia, the ruling Romanov family was “Shot without Bourgeois Formalities but in Accordance with our new democratic principles."

So it is not as though there was nothing to worry about in 1919. But like today, these worries enabled anti-democratic thinking in the United States, and they were far more focused on identifying conversations about sex and race as part of an unwanted revolution.

And this is why. At the time of Goldman’s arrest in 1917 for encouraging men to resist the draft and her second arrest during the 1919 Palmer Raids that prompted her deportation hearing, Goldman was also embedded in the fight for women’s social, sexual, and political equality. This commitment coincided with an increasingly militant women’s suffrage movement.

Voting, of course, was not at the top of the list of anarchist demands. But other personal freedoms threaded through an American feminist struggle in its first political phase: the right to contraception, the right to free love outside of marriage, and the right to love someone of the same sex, a condition that, by the 1890s, physicians and lawyers had begun to call homosexuality. All of these sexual freedoms implicated speech. Thus, it was no accident that the American Civil Liberties Union was founded by a group of activists in Greenwich Village who believed that constitutional guarantees of free speech and freedom of association inferred the right to sexual autonomy.

These were all things that Emma Goldman believed and participated in, and which allowed the Department of Justice official in charge of the Palmer raids, J. Edgar Hoover, to declare that Goldman was not just an anarchist but a sexual pervert.

And legally, Goldman violated the nation’s laws about sexual speech, not because of her actions but because of yet another piece of federal legislation: the 1873 Comstock Law, named after anti-vice crusader and postal inspector Anthony Comstock. This statute (which is still on the books) makes it a federal crime to send printed erotica, abortifacients, birth control, and sex toys (otherwise known as “rubber goods”) or any information about these things through the mail. The law also criminalized personal letters that contained information or descriptions of sex or sex products.

By 1919, Emma Goldman was guilty of all these things. She spoke, wrote, and published the writing of others on federally prohibited topics in her magazine, Mother Earth, founded in 1906. Goldman also wrote about them in her private correspondence. And while she is far better known for her anarchism than for her feminism, in 1914, Goldman—in an intimate and open partnership with a male doctor who specialized in the treatment of venereal disease—became a passionate supporter of Margaret Sanger’s campaign to make birth control available on demand. She devoted her 1915 speaking tour to contraception. Illegally distributing copies of Sanger’s pamphlet, “Family Limitation,” Goldman was arrested in 1916 before one of her engagements and convicted of violating the Comstock law. Because paying the fine would mean recognizing the government’s authority to regulate her speech, she chose instead to be committed to a workhouse for two weeks.

So, by the time Goldman was arrested in 1917 under the newly enacted Espionage Act for encouraging Americans to resist the war (a position she maintained until she died in 1940), her insistence on freedom of speech went well beyond the purely political. In effect, Goldman and feminists like Sanger had redefined the political to include resisting government infringement on women’s freedom to discuss, disseminate information about, and freely make decisions about their bodies.

I want to emphasize the peculiar parallel with our own time: early 20th century reformers and lawmakers fervently believed that enforcing prohibitions against birth control, homosexuality, and abortion (which most states had criminalized by 1910), required that speech about these things be outlawed as well.

In 1919, when Goldman was deported, it was, however, perfectly legal to write, speak and disseminate written information through the mail about a non-existent problem, “white slavery.” The Comstock law also prohibited conversation about a social phenomenon that was increasingly visible in cities around the globe by the early 20th century, young people pairing off with others of the same sex. In 1924, German immigrant, U.S. Army veteran, and postal worker Henry Gerber launched the first campaign for gay liberation called the Society for Human Rights: Gerber was arrested and tried as a “degenerate” when a member’s wife discovered the organization’s newsletter. Ultimately, Gerber pled guilty to local misdemeanor charges (after bankrupting himself by bribing local officials) and was not deported.

A little more than 100 years later, we have seen a revival of government efforts, now at the state level, curtailing or reversing social change through characterizing speech about race, sexuality, and gender as perverted and subversive. Nineteen states have already or are prepared to outlaw abortion should the leaked SCOTUS draft opinion overturning Roe v. Wade prove to be the final decision. Notably, many of these laws bar speech and written communication that encourages or even gives information about the procedure. Similarly, laws aimed at criminalizing health care for transgender youth and alleviating racial, sexual, and gender discrimination through education are bolstered by various prohibitions on speaking to children about gender or allowing children to talk to adults confidentially about their own gender.

The groups targeted by these new speech codes? Teachers (who have now been labeled potential sexual “groomers”), librarians, and health care providers.

And last but not least, now that deportation is a keystone of American immigration policy and an obsession on the right, those who are not yet citizens cannot call attention to themselves through acts of dissent and protest without risking Emma Goldman’s fate.

Short takes:

What is the meaning of the Peter Navarro subpoena delivered by the D.C. grand jury investigating the January 6 insurrection? According to Josh Kovensky of Talking Points Memo, it’s a sign that federal prosecutors are zeroing in on Trump and his cronies: Navarro (who is also currently in contempt of Congress) was allegedly the conduit between the West Wing and plotters outside the White House. “The move comes after six years of investigations into former President Trump and his inner circle that ended with the indictments and convictions of a select few of his associates — including former campaign chairman Paul Manafort and adviser Roger Stone — but failed to touch the former president himself,” Kovensky writes. (May 31, 2022)

The SCOTUS leak investigation is primarily out of the news. But it continues. According to Joan Biskupic at CNN.com, court clerks were alerted yesterday that the SCOTUS marshall's office will examine their phone records. “Some clerks are apparently so alarmed over the moves, particularly the sudden requests for private cell data, that they have begun exploring whether to hire outside counsel,” Biskupic writes. (May 31, 2022)

Why do San Francisco’s corporations hate progressive district attorney Chesa Boudin—and why have they pumped $5.1 million into a recall campaign? Answer: it’s not about Boudin, and it’s not about crime. It’s about Republican mega-donors trying to break the back of one of the nation’s most liberal Democratic organizations. “The recall’s top funder is the Republican billionaire William Oberndorf, who donated $3.7 million to federal candidates in 2020—mostly to Republicans, including Senators Mitch McConnell and Tom Cotton,” Christopher D. Cook reports at The Nation. (May 28, 2022)

Well done! The fact the Comstock Laws are still on the books should disturb anyone who believes in a free, democratic society.

Excellent review and scary parallels. Goldman being a woman didn't help either. The jailing and brutalization of suffragists in 1919 to censor their silent speech, and Susan B Anthony's guilty verdict declared by a judge after dismissing the jury are examples of how the state waived legal norms when it came to censuring women's activism.