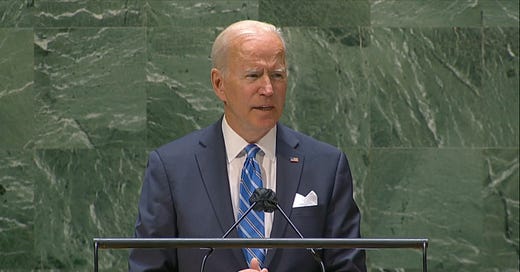

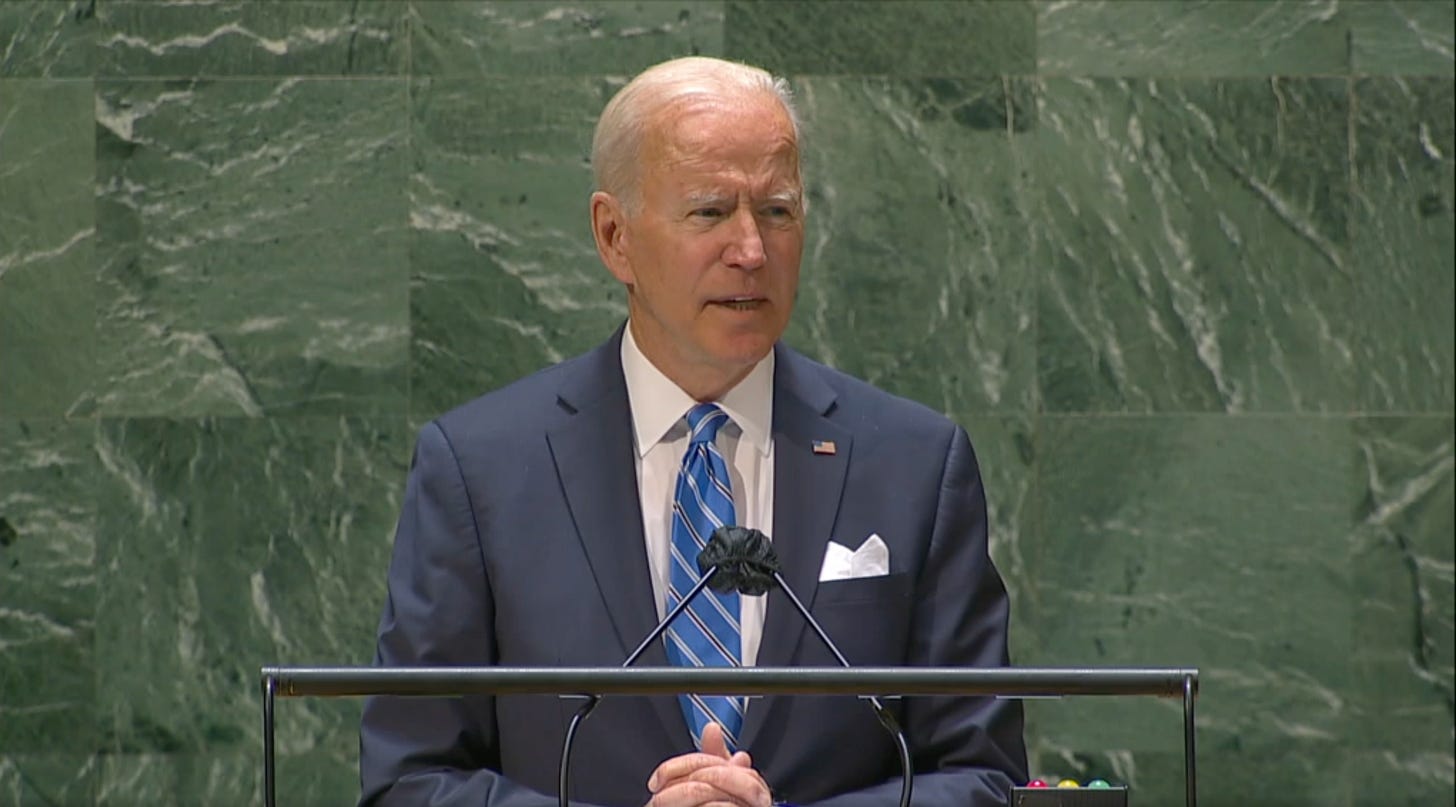

The Biden Doctrine

Calling for strength in unity at the United Nations, Joe Biden redefines the meaning of American realism to include an idealistic vision for the rest of the world

Today is officially the first day of fall. But before you rush out to Trader Joe’s to shop for pumpkin spice everything, please:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Political Junkie to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.