When a Childcare Center Became a Political Movement

You've seen the famous photo of community organizer Dorothy Pitman Hughes with Gloria Steinem, but this new biography by Laura L. Lovett tells you who she really was

Do you know someone interested in women’s liberation, Black feminism, and community organizing? Then, by all means, encourage them to subscribe and:

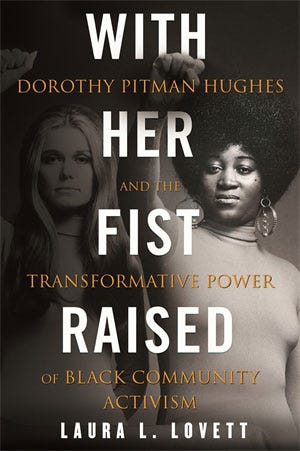

Laura Lovett is a distinguished feminist historian at the University of Pittsburgh who has spent her career writing about activism, African American women, childhood, and youth. In With Her Fist Raised: Dorothy Pitman Hughes and the Transformative Power of Black Community Activism (Beacon Press, 2021), Lovett brings all of her expertise to bear on a feminist who has been frequently seen in the iconic photograph on the book’s cover—but rarely heard about from historians. Last week, I had a chance to sit down with Laura and discuss this extraordinary activist, how Lovett came to write the book, and why Pitman-Hughes should be at the center of any story about Black Power empowerment and the American women’s movement in the 1970s.

Claire Potter: Laura, tell us the story of Dorothy Pitman Hughes. Who is she, and why is she important?

Laura Lovett: Dorothy Pitman Hughes is a community activist who is most well-known for the photograph that she made with Gloria Steinem with their fists raised. But she has been unrecognized for her contribution to all sorts of movements: the women's movement, the black power movement, community control, and daycare, are a few. She was one of the first people to name the process we call gentrification that begins in the 1980s in New York City. Her narrative helps us understand the intricate relationship between movements that are often seen as entirely different.

CP: And she wasn't originally a New Yorker, was she?

LL: No. She is from a tiny little town outside of Lumpkin, Georgia, an African-American community. She goes to New York; she becomes a singer. Her family does, too: her brother and three sisters all imagined that singing is a way out of the poverty and racism of rural Georgia. She winds up in New York, initially employed as a domestic worker and as a nightclub singer.

Dorothy initially signs up with an agency that pays for her transit up to New York and places her in a home as a domestic worker. But she's somebody who can quickly figure out how to create and navigate local connections. She's singing at night. She winds up moving in to work for the owner of Maxwell's Plum, an important New York City nightclub in the 1960s and 1970s. While she's in this space, she connects with all sorts of political movements. By the early 1960s, she is working for the Congress of Racial Equality as a part-time secretary, still singing at night and working as a live-in domestic on Long Island.

CP: What kind of politics or activist experience did she have before she came to New York?

LL: Her origins are in a Black community that's not afraid to face down white violence. Dorothy’s father worked in a timber community and owned his own truck, which meant that he had status within a community that valued independence. Many of the mill workers where her father is moving logs were in the Ku Klux Klan. Her grandmother winds up taking a job as a cook on a site where Klan meetings are organized, and she uses her position to warn the community about impending violence. Dorothy’s mother's twin sister was a leader of the women's community in the local church.

CP: And Pitman Hughes also became a single mother, too, right?

LL: Yes. One of the things that happens to her in New York is that she develops a problem with her menstrual cycle and goes to a gynecologist, a white gynecologist, who tells her that the way to solve the problem is to have sex.

CP: I was stunned by that.

LL: I think Dorothy agrees with me that it's important for people to understand how confused the narrative around sexuality still was in the early 1960s. This is something the women’s movement would have a big impact on. A gynecologist tells her to have sex. She has never had sex. He assumed because she's an African-American woman in New York, about her sexual knowledge. But she doesn't know about birth control.

While Dorothy is singing one night, she selects a man because he’s the best dancer, and she gets pregnant. She becomes a single mother of a daughter, Delethia. This is '63-'64.

CP: Having a child, and being a working woman, causes Pitman Hughes to put childcare at the center of her activism.

LL: Yes, although before that, she gets married. Through her job at Maxwell's Plum, she meets up with an Irish organizer, a member of the IRA named Bill Pitman, and they hit it off. His politics are as radical as hers. They get married, and they have a daughter, and now she has two children. She's still singing at night, but she is often at home during the day at her apartment on the Upper West Side, near West 80th street, at the time a pretty rough area.

Dorothy realizes that many kids were on the street or being taken care of by older siblings in this hard-hit neighborhood, and there is a need for a community resource. She knocks on doors and says, "I'm at home with my kids during the day. I'll take your kids too." She winds up gathering a number of families together who become the core of a daycare center. Soon, she winds up negotiating with the owner of what's called at the time a “welfare hotel,” where New York City put up families who were on welfare because it was expensive to build adequate public housing.

It's a pretty rundown building, but she manages to negotiate a two-room space in that center. For her, the center must be a place that is welcoming to people of all classes but especially working-class families. She's really intent on creating a resource for the community. She charges $5 a week, and she won't institute a graduated rate because she believes that if she does that, people will wind up feeling like they have kind of more rights to more resources. For her, this must be a community site that allows for parents and children to work together. She's also adamant that the parents should run the center. They create a governing board, make hiring decisions, and decide what's going to be taught.

CP: And this is how Pitman Hughes meets Gloria Steinem, right?

LL: Yes. Steinem has just decided that she's going to work for New York magazine because it's the only place that she can actually write a political column. She's writing a series. One of the Office of Economic Opportunity employees working with Dorothy persuades Steinem to do a story on what is, by 1969, called the West Side Community Alliance.

Steinem visits, and she can see that this isn't just a childcare center. Dorothy has created an afterschool program. She is addressing parent education. She's active in the conversation about tying childcare to welfare. She asks questions about the purpose of welfare: if somebody has access to it, can they be allowed to go to school or train for work? She realizes that certain food stores in the area raise the cost of food on the day that welfare checks come out, and she exposes that. She winds up using some of her benefactors to create what may be one of the first official domestic violence centers.

Steinem does a piece about her as a community activist, but they wind up realizing they have a real political and personal connection around feminism. It's in light of that, after the story comes out, that Dorothy reaches out to Gloria and says, "Let's go do some talks. Let's be up on stage." It's a moment when Steinem is interested in thinking about the role of Black Power in the women's liberation movement, and what Pitman Hughes says is: “We have very different approaches to this issue. Still, I think it's important to start modeling a conversation around shared agendas and shared issues.”

CP: But it's Pitman Hughes that initiates the partnership.

LL: Yes. Dorothy is somebody who likes to speak. Gloria Steinem is a journalist, she likes writing, but he does not like speaking in public. When they made appearances together, for the first, I think, couple of years, Steinem was always nervous. Sometimes Dorothy would have to hold her hand to get her up on the stage. In fact, she really coaches Gloria, who then becomes an extraordinary speaker. But it’s Dorothy--a singer and a community organizer--who persuades her that this is something she can do.

CP: What is Pitman Hughes’s trajectory after this moment when she's touring the country with Steinem and building a national profile for work she's doing?

LL: Dorothy and Bill Pitman part ways amicably. She marries Clarence Hughes and has a third child, who she names Angela—for Angela Davis, whose legal defense she had raised money for. But three kids is too much work for her to be on the road. Then, the state of New York introduces uniform standards for child care and regulations and about who can have access to it. She organizes about 150 childcare centers across the city to push back, but she gets moved out of child care herself because she doesn't have a college degree.

Then she realizes that political organizing--and this will be antique and strange to younger people – relies on copy centers. Right? You had to have a place to make flyers back in the old days before digital media. She decides that she's going to open a copy center in Harlem. She calls it Harlem Office Supply. It's a combination copy center, office supply, and Black history bookstore, right on 125th Street. It was another kind of community center.

CP: But then the chain stores start moving into Harlem. How does that happen?

LL: Right. So she builds this business and actually helps to elect Bill Clinton as President in 1992. Clinton comes up with a program based on something he had done in Arkansas called The Empowerment Zone, which was supposed to increase employment for the poor, and in this case, Black employment. Dorothy imagines it as an investment in Black economic development based on small businesses, but it doesn't. It means just jobs, as many as possible. So that’s when the chain stores start moving in.

Around that time, she invests in all sorts of things. She creates a Black women's connection program in Harlem, and she buys the rights to the Miss New York City Pageant.

CP: And the pageant must have put her at odds with some of her old feminist allies.

LL: It did. So I knew I had a book when I interviewed Dorothy and Gloria together at the re-photographing of that picture that had been taken for Esquire magazine in 1971. The last question I asked the two of them was, "Were you always on the same page?" To which Gloria Steinem said, "Yes." And Dorothy said, "Well, actually…." and then talked about how nervous she had when she bought the New York City pageant. She bought it because her middle daughter loved Miss America and really kind of identified herself and her self-worth in terms of the Miss America pageant. What Dorothy decided to do with the pageant was to challenge white notions of beauty.

She was a businesswoman. She bought the franchise, runs the local pageant, and of the 10 finalists, I think eight were women of color. She travels to Atlantic City with her daughter, who was so, so excited to go, and winds up filing a lawsuit against the Miss America corporation because of the racism she experienced as one of the only female, and certainly the only female African American, pageant franchise owners. But it matters. A couple of years after she runs this pageant, Vanessa Williams is selected as the first Black Miss America.

CP: So back to Harlem. What happened with the Empowerment Zone?

LL: She imagined it was an initiative that would help Harlem grow, but it wasn’t. Congressman Charlie Rangel, who she had been supporting, makes it clear that this program is not for her. But she opens her business, Harlem Office Supply, anyway, selling shares at a dollar each because she really wants it to be a symbol of community economic empowerment. But Rangel thinks she's organizing a political faction against him. He authorizes a grant for the Abyssinian Baptist Church, which buys a Staples franchise. They open it almost right across the street from Harlem Office Supply. It employs more African Americans but is not about Black economic empowerment. Dorothy winds up having to sell the store, and she moves in with her daughter.

But she saved all those shares. The historian in me was really excited when she told me she had hundreds of boxes in her daughter's garage because I thought: "Yes! this is the gold mine." It turns out that almost all of those boxes were filled with identical pieces of paper: the shares that hundreds of people had bought, at a dollar apiece, as an investment in Harlem Office Supply.

CP: It's a devastating story.

To switch gears: I wasn't surprised, given Dorothy's vision for interracial activism, and her intimate life and friendships with white people, that she embraced a white biographer. But what did you think about your role in writing the first biography of this important African American figure?

LL: I was intimidated by the prospect. But it came about because I had co-edited a book on the history of the feminist television show, “Free to Be You and Me,” which was filmed at her daycare center. I was at an event talking with her about who was doing her story because the image-- the picture of Dorothy and Gloria together with their fists raised symbolize--has proliferated, but knowledge about her has not. There are t-shirts, I have jewelry pieces with this image: it speaks to Dorothy’s intersectional vision of what was possible in feminism. "Nobody's doing this,” she said. “You should write it." When we agreed to work together, the place she insisted I meet her was the small town in Georgia that she's from. She wanted me to know who she was, where she came from, and what was important to her.

I started recording interviews and helped to work with her on making an archive: you always have to find a way to check the story, especially when you're basing a book on oral histories. A feminist like Gloria Steinem knew that what she was doing was important as she did it and saved the paperwork. But Dorothy was always actively working in the community and wasn't necessarily documenting what she was doing.

And sometimes, she was excluded from the record by others. Dorothy was part of the Comprehensive Child Development Bill's organizing in 1972. Still, she appears nowhere in any of the text of the Senate hearings or the answer to Nixon's veto. It was only by looking through the Congressional Record, hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of pages, that I even found a photograph of Dorothy at the Senate hearing with the six children who testified. But her name isn't mentioned.

As I told Dorothy, I think I may be her first biographer, but I won't be the last. In writing the book, I have helped collect materials to understand her complicated relationship with all these different organizations, movements, programs, and events. And that allows us to tell a much more complex story about this time period.

CP: A more complex story that we need right now. Thank you, Laura.

Claire Bond Potter is Professor of Historical Studies at The New School for Social Research and co-Executive Editor of Public Seminar. Her most recent book is Political Junkies: From Talk Radio to Twitter, How Alternative Media Hooked Us on Politics and Broke Our Democracy (Basic Books, 2020).

What I’m reading:

Is Instructure, the company that owns the learning management system Canvas, FERPA compliant? These Rutgers professors don’t think so. (The Nation, April 22, 2021)

Popular culture is high on the Black Panther Party, but as Santi Elijah Holley writes at The New Republic, actual Panthers have been forgotten. (April 22, 2021)

Brearley student Yassie Liow responds to the letter from “Brearley Dad” that protested anti-racism initiatives at her school. (The Iris, April 20, 2021)

Delighted to know about this much-needed biography of Dorothy Pitman Hughes!