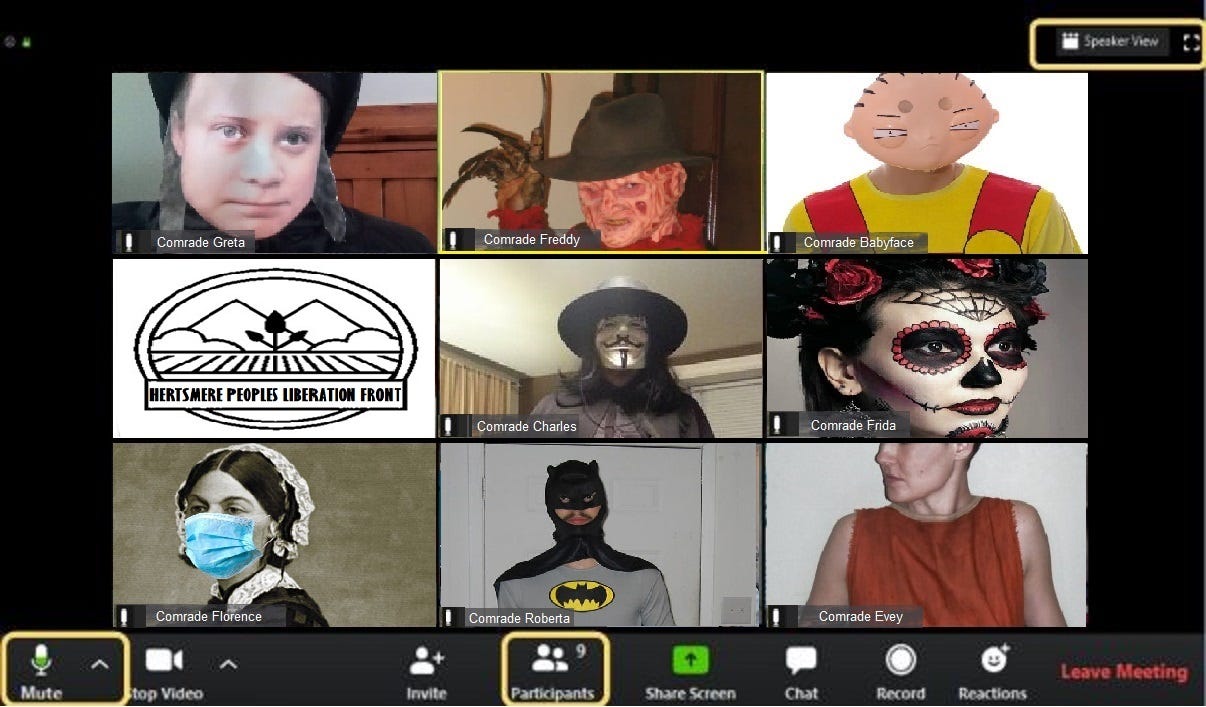

The Zoom Compromise

When we finally get back to campus, let's admit that, necessary as it was, the long-term damage from putting whole universities online has been significant

This post is a quick one, friends: it’s the first week of school, and I am slammed. If you have friends who like newsletter writers who complain, please:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Political Junkie to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.