This November Can Be the Democratic Party's Gettysburg

On July 4, 1863, the Union Army--and a young patriot from Massachusetts named Charles Potter--saved democracy. We can do it again

Every July 4, in the damp heat of a Pennsylvania summer, H. Phelps Potter—father, husband, Eagle Scout, military veteran, former intelligence officer, and physician—used to raise the Star Spangled Banner outside our house. I will never forget him, in a sports shirt and khaki shorts, fiddling with a complex series of knots, ones that only a Boy Scout would know, to get our flag hanging just right.

Dad passed away 25 years ago this month, but as a man who collected shelves of books about the Civil War, I think he would like this post, which is dedicated to him. If you know someone else who would like it, please:

And please read all the way to the bottom: I’ve got an ask.

It’s fair to say that July 4, 1863, was a big day for the Union Army and the nation.

It can hardly be a cosmic coincidence—historians of the Civil War know more about this than I do—that the Confederate Army came as close as it ever would to permanently splitting the Union on the 87th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. A month after a bruising victory at Chancellorsville on May 6, General Robert E. Lee slipped out of what had been a two-year stalemate in the trenches of Virginia. He hoped to break the Union Army’s back and the federal government’s spirit by marching his army through a virtually undefended Maryland countryside, drawing the Northern army into Pennsylvania, and dealing it a crushing blow.

By June 26, a portion of Lee’s forces occupied Gettysburg, 140 miles from Philadelphia and 35 miles from Pennsylvania’s state capitol, Harrisburg. On the way, they seized 1,000 free Black people and transported them South into slavery. Lee ordered his troops not to loot: instead, they paid for commandeered food, horses, and shoes in worthless Confederate dollars.

As the Army of the Potomac pulled back to Pennsylvania to stop the Confederate advance, Charles Potter, a private soldier with the 10th Massachusetts Volunteers (who may or may not be one of my ancestors), marched north. Potter and other men from the western counties of the state had mustered in at Springfield on June 21, 1861. They had fought at Chancellorsville, and nearly every major battle in Virginia, among them Fair Oaks, Seven Pines, Antietam, and the disastrous “Mud March” offensive in January 1863, where it rained so steadily that Confederate snipers picked off Union soldiers as their boots were sucked into the saturated earth.

Potter and his comrades set up camp in Manchester, Maryland, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Joseph B. Parsons, where they were held in reserve as part of VI Corps until Lee’s strategy and positions became evident. As they rested and resupplied, Potter may have been relieved to hear that General Joseph Hooker, who had allowed Lee to slip away and failed to engage as the Confederates moved north, had offered his resignation on June 28. President Lincoln had now put General George Meade, a Philadelphia-born engineer, West Point graduate, and veteran of the 1848 Mexican-American war, in command.

As the Union Army scrambled into position in central Pennsylvania, Lee positioned his forces in a 30-mile arc and warned his generals to wait to attack until he had fully reinforced his battle line. But one of Lee’s subordinates couldn’t wait. Confident that his sector was only guarded by a local militia and he could quickly seize higher ground, at 5:00 a.m. on July 1, that general sent two infantry brigades to capture Herr Ridge, McPherson Ridge, and Seminary Ridge to the west of Gettysburg.

It was a terrible miscalculation. Union troops, many of whom were in reinforced positions, fought back hard while, as Lee attacked across his front, Meade rushed reserves to the scene to fill gaps in the line and strengthen depleted brigades. An urgent wire to Manchester mobilized Charles Potter and his comrades, who marched 37 miles in 17 hours, arriving at the battlefield on the afternoon of July 2. There, they were rushed into action to support a battered XII Corps. Potter’s regiment was tasked with retaking positions at Culp’s Hill, lost by a skeleton force when Meade had redeployed the bulk of its defenders to a critical battle at Little Round Top.

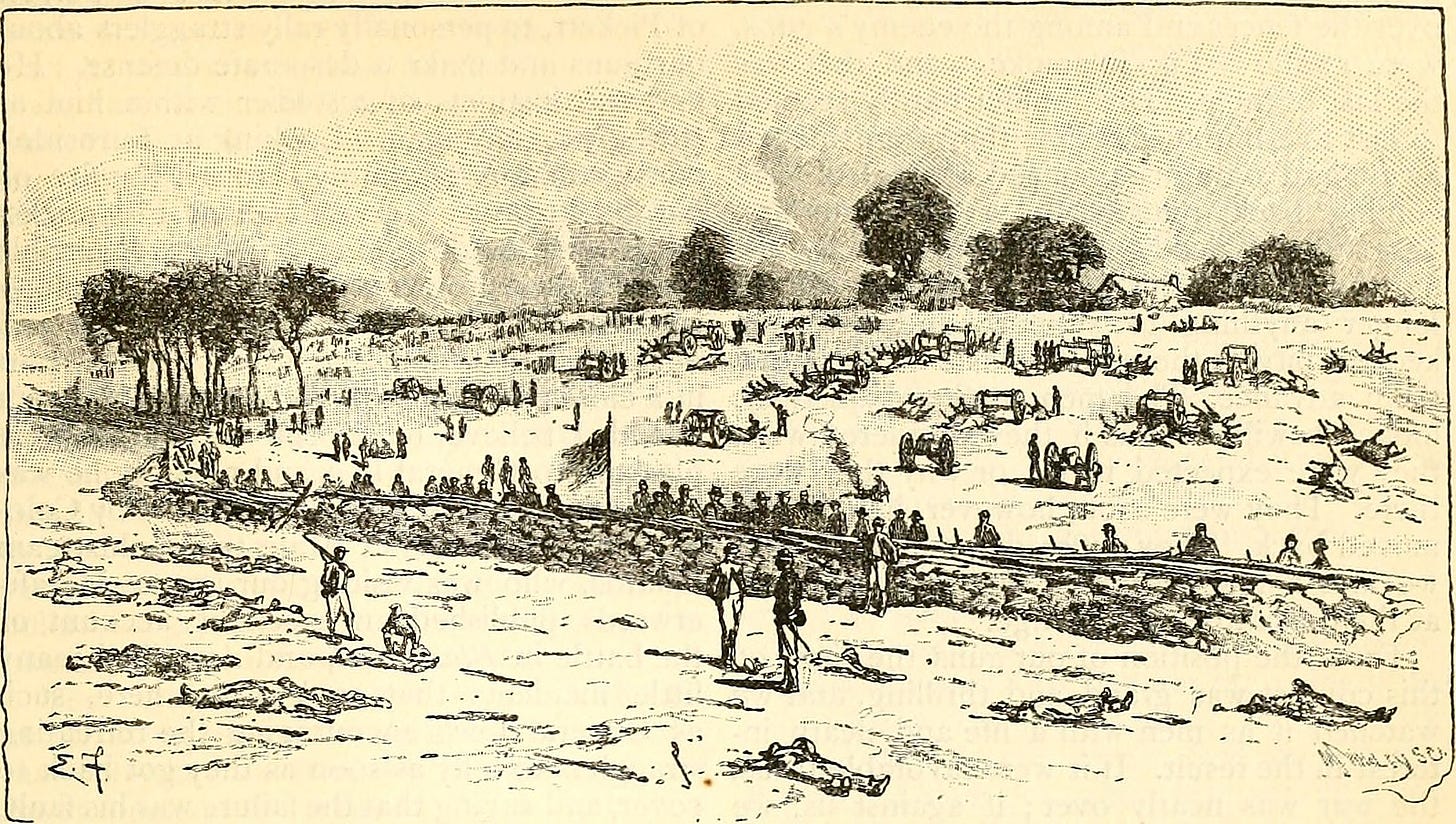

Although Lee and his generals initially advanced on July 1 and 2, they did so at a terrible cost, suffering a third more casualties than the Union Army in a battle that would see close to 50,000 men on both sides killed, maimed, and wounded. Finally, on July 3, XII Corps retook Culps Hill: an exhausted Potter, peering over the battlements, would have seen heaps of Confederate and Union bodies, bloating and shifting in the sun.

Just a mile to the east, Potter would also have heard the scream and thump of Confederate artillery pounding Union forces occupying Cemetary Ridge, where three significant highways converged. Those highways led north: occupying them would have allowed Lee to split the Union forces in two, possibly surround them, and give his troops a clear path into abolitionist New York State and New England.

But on Meade’s orders, Union artillery undamaged in the barrage remained silent, and defenders on Cemetary Ridge were ordered to hold their fire. Intended to reserve ammunition as the Confederates spent theirs, Meade hoped to lure Pickett into believing that the defenders had been so weakened that he could take the position with a simple infantry attack. Meanwhile, Union soldiers waited grimly, crouching behind a low stone wall erected and maintained by generations of Pennsylvania German farmers. Poorly-supplied Confederate troops typically saved their ammunition for close-quarter fighting, but, as one Southern officer who survived the battle said later, “I had never before seen the Federals withdraw their guns simply to save them up for the infantry fight.”

So, at 3 p.m., with little return fire coming from Cemetary Ridge, on Lee’s orders, Pickett’s men charged. “On they came whooping and yelling on double quick time their artillery playing on us all the time,” recalled one Union artillery officer. “When [they were] within about 300 yards of us, we got the word to fire.…We mowed them down like ripe grain before the cradle. They could not advance under our galling fire and began to recoil.”

In the following hours, half of Pickett’s forces were killed, wounded, or captured, many from devastating grapeshot and explosive canisters. Others died in hand-to-hand combat with New Englanders from Vermont’s Second and a Pennsylvania volunteer unit known as the Philadelphia Brigade. When Pickett pulled back what remained of his men a few hours later, he received a second set of orders from Lee: to ready his division to defend his position at the center of the Confederate line in preparation for the inevitable Union counterattack.

Pickett’s alleged response consisted of a single, bitter sentence: “General, I have no division.”

With that, on July 4, Lee knew he had failed. He negotiated a truce that allowed him to collect his wounded and begin marching his exhausted, hungry, battered troops back through Maryland to Virginia. On that same day, Vicksburg, Mississippi, the rail hub that linked the eastern and western sections of the so-called Confederate States of America, fell to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman after a months-long campaign.

But Gettysburg also has an ugly coda. A week later, as Charles Potter and his fellow soldiers chased Lee’s army back to the Rappahannock in Virginia, civil violence erupted In New York City on July 11. Working-class white men, drafted against their will and goaded on by Copperhead politicians, launched three days of murder, looting, and arson against that city’s free Black people, abolitionists, and interracial families. Then, in one of the Draft Riot’s most brutal events, the mob burned the Colored Orphan Asylum before Federal troops arrived from Gettysburg to end the violence.

So, on July 4, it is essential to remember what a harbinger of the future the Civil War was, ranging from new, industrial methods of war-making to race and politics.

First, the artillery barrage, which we see playing out in Ukraine today, came of age as a modern strategy for subduing the enemy, blurring the line between combatants and non-combatants, and using death rained down from above to demoralize the enemy. Before they surrendered, the citizens of Vicksburg had spent months living and starving in caves and dugouts around the city as Sherman’s artillery pounded their besieged town. He would use the same tactics against Atlanta in the spring of 1864, creating a refugee crisis that clogged the roads in and out of the city and made it nearly impossible to resupply the Confederate army. By World War I, artillery would be the defining feature of modern warfare.

Second, Southerners’ determination to break the political compact between colonies made in 1776, a promise affirmed in 1781 with the Articles of Confederation and again in 1788 with the United States Constitution, has never ceased. Today, the flames of disunion are, once again, at the gates of our democracy, as radical conservatives, aided by the Supreme Court, seek to pry their states away from federal rule.

And finally, the calamity of the New York City Draft Riots presaged a century of white mass violence against free Black communities and should remind us that we still underestimate how quickly white populist rage takes the form of lethal hostility toward people of color.

The Confederates were defeated, but they never went away. Their spiritual and political descendants of the Draft Rioters mustered in Charlottesville in 2017, and behind Trump’s failed coup on January 6, 2021. They are now, in some places, literally in charge of the Republican party, heavily armed, and they have a plan: excising non-white histories from the curriculum, excluding immigrants of color from citizenship, promoting Christianity as the national religion, and controlling sexuality and gender expression. This is what “family values” has come to mean.

Pundits keep warning about a new Civil War: but what if it never ended? And what if it no longer takes violence to overturn a democracy?

Just as the Confederate States of America claimed legitimacy from a false reading of the Constitution, a radically conservative Supreme Court majority is now the primary weapon in a new civil war fought out in the courts as well as in the streets and at the ballot box. In the last weeks of June, decisions toppled precedents on abortion, separation of church and state, state restrictions on guns, and the rights of those taken into police custody. And across the country, multiple political candidates embracing Donald J. Trump’s Big Lie of a stolen election are on the ballot and could be in Congress by January 2023.

It’s a new kind of rebellion, friends, a civil war where American institutions, not armies representing breakaway states, are being turned against the founding ideals of our nations—the ones Charles Potter fought for.

The upcoming Congressional elections in November are our Gettysburg, and it is up to us whether we stand and fight or whether we retreat. It’s a choice, not a fate. So I ask you, on this July 4, to pledge that you will do your patriotic duty to this nation: pick a Democratic candidate and don’t just give money—work to get that person elected. It might be a school board, city council, county-wide, state level, or federal race: surely you understand that all political offices are essential now.

Like Charles Potter, who finally mustered out on July 6, 1864, and returned to his home in Western Massachusetts, we’ve got a nation to save.

Short takes:

As two city officials in LLano, Texas, prepared to read the Declaration of Independence, a group of townspeople assembled. A group, including fired county librarian Suzette Baker, sat quietly in folding chairs reading books on race, sexuality, and gender that culture warriors culled from public library shelves. As Alejandro Serrano of the Houston Chronicle explains, the protesters have filed a federal lawsuit against county Judge Ron Cunningham, who authorized the censorship, and was one of the event’s leaders. Defendants also include “county commissioners, and library officials” who put the book bans into effect last summer, Serrano writes, “beginning a campaign of `censorship and viewpoint discrimination by removing and restricting various books.” (July 2, 2022)

There are many reasons why your local fireworks display may have been canceled or rescheduled, but none is Joe Biden’s fault. At NPR, Taylor Hutchison and Kathryn Fox explain that shortages of qualified technicians are as much to blame as inflationary prices and shipping delays. “The demand for licensed professionals on the Fourth of July is not anything new in the fireworks industry,” they write. “But making a comeback after the pandemic has affected the ability to fulfill demand.” (July 2, 2022)

At FiveThirtyEight.com, Nate Silver explains why the GOP may win the House—but not the Senate—in November 2022. It is too early to tell how anger about Roe will play out in either chamber. Still, by making a series of unpopular decisions, “the Supreme Court has in some ways undermined one of the traditional reasons that the president’s party tends to lose seats at the midterms,” Silver writes. “Typically, voters like some degree of balance: They do not want one party to have unfettered control of all levers of government. But the Supreme Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority, is a reminder of how much power Republicans have even if they don’t control the White House.” (June 30, 2022)

Gosh Howard, I could use a good transgender drug dealer. Sounds like you know a bunch of them. Help a brother out.

Of course you were in this round table! Maybe I ought to do a search before making another historical fiction recommendation, but I’m just gonna go for it, because I’m utterly obsessed with it, and have found that hardly anybody knows about it. Have you watched Black Sails? On Starz? It’s queer pirates and escaped slaves against the British Empire, and, really, all of “civilization”, in Nassau, approx 1705-1715. About a third of the characters are based on real historical figures — the pirates Anne Bonny, Jack Rackham, Charles Vane, Teach and Hornigold (who was also a Jacobite), the maroon queen Nanny, and colonists including the Guthries and Woodes Rogers; a third are well-known fictional characters as it’s a prequel to Treasure Island — Flint, Silver, Bones; and about a third were created for the show, including some great women characters. Obviously, the American Revolution didn’t happen for another 60 years and the Civil War not for another 160 years, so they don’t destroy England, but it’s a thrill to watch them try! The acting, writing and production is sublime. The relationships are natural, compelling and complicated. The history? At first I thought it was as wishful as in Paradise Square, and (in season 3 and 4) similar in its hopes of interracial and sexual freedom and utopia, but as I delved a bit into labor conditions in the royal navy and merchant vessels, matelotage, and maroon uprisings, not to mention graphic design history made by the creation of the Jolly Roger, I realized it’s full-on fiction, but not fantasy. There’s really nothing like it, I don’t think (please tell me if I’m wrong!) — historical fiction that’s not about royalty or the aristocracy, but rather about resistance to it. Plus sex. (Btw, Black Sails makes some stupid GoT-style moves on that front in season 1 but got schooled or pushed Starz away successfully by season 2.) I haven’t succeeded in getting many to watch this damned incredible show — despite how serious it is l, I guess people assume it’s dumb swashbuckling — but if I’ve convinced you, or you’ve already seen it, I’d love to know what you think!