Will it Always Be September 12?

Although we have repeatedly vowed to "never forget," it seems that many Americans may have done exactly that. And it's ok.

It’s a rainy Monday here at the beach, but it’s nice to see you again! As always, if you know someone who would like today’s post, please:

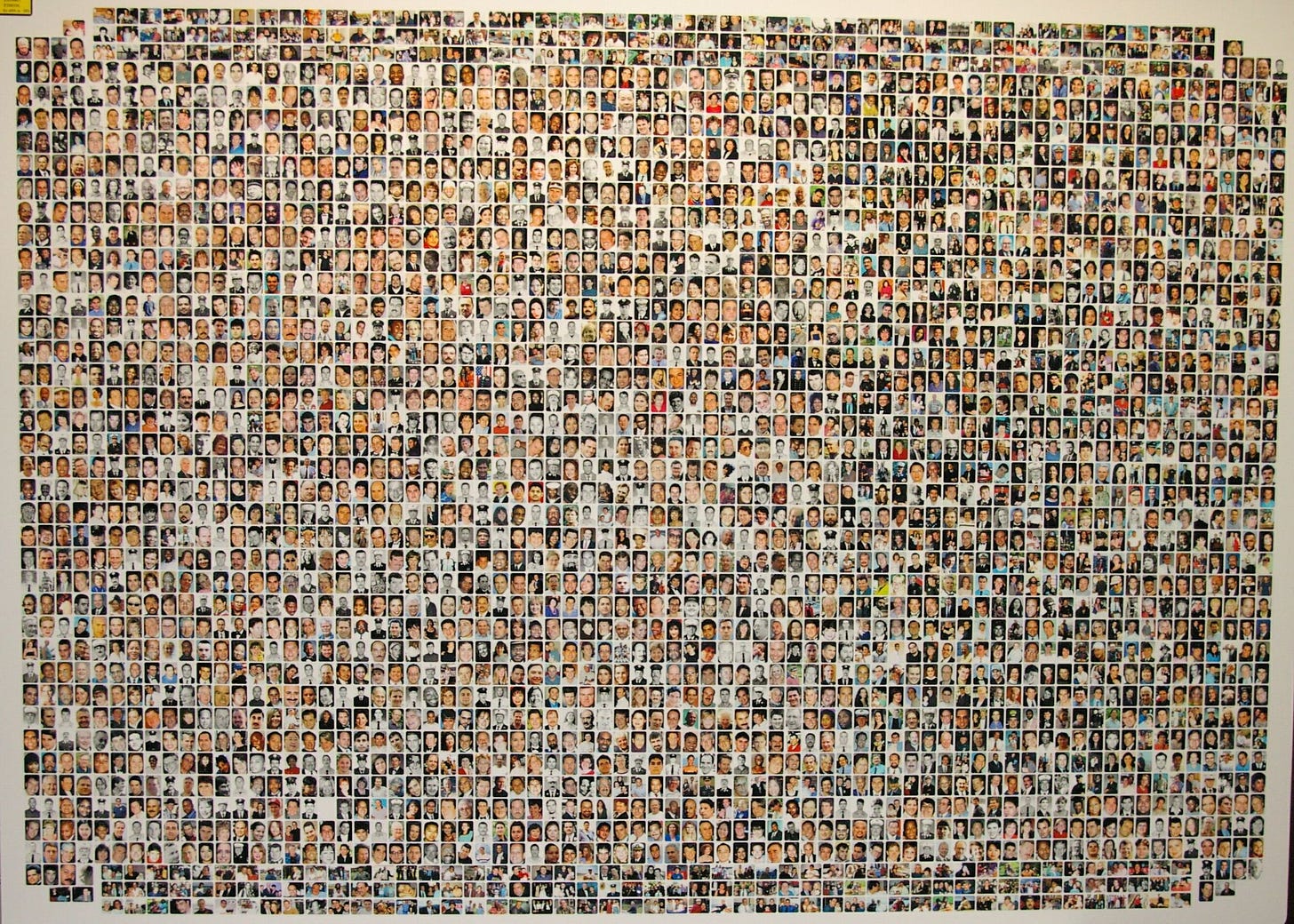

September 11, the anniversary of the three terrorist attacks on the United States, passed almost unnoticed this year. Granted, it was the 21st anniversary, which is not a milestone. But, more importantly, the media world was also oversaturated with coverage of the English Royal Family and United Kingdom politics: Queen Elizabeth II began a long, winding passage to her final resting place as pundits wrestled with the meaning of monarchy, surely one of the more idle (although endlessly fascinating) topics if you are not an English taxpayer. Then, the Ukrainian Army crashed into Russian lines and splintered them, advancing to the border in some areas as panicked soldiers abandoned their equipment, stole bicycles, and hot-footed it back to the Motherland. And football season began.

Yet, you would think that if Americans wanted to remember the day they promised to “never forget”—and if news corporations thought there was a market for September 11 memories—yesterday’s news coverage would have been different. Although Joe Biden laid a wreath, and there were memorial services around the country, these events received little to no news coverage. My social media feeds, usually full of elegant short essays about where people were, how they learned about the planes crashing into the Twin Towers, and what they did, contained almost no posts on the topic, and the ones that did pass through my feed seemed—obligatory. I was not moved to write one either: I have said those things, felt those feelings, and I no longer have anything else to say on the topic.

The question is: why? I don’t know, but here are some theories.

There has been so much to distract us, and those things have included a lot of death. First, in that 21 years, we have had two failed wars that killed nearly 500,000 people in Iraq and Afghanistan, over 6,000 Americans in Afghanistan, and more than 4200 in Iraq. In addition, tens of thousands more American lives have been ruined because of military service in these war zones. Second, mass shootings skyrocketed after 9/11. Third, there were four years of Donald Trump, which felt like an ongoing national emergency, topped off by the first coup attempt broadcast live on TV. Finally, there were two years of the Covid-19 crisis, during which the daily death rate sometimes exceeded the casualties on 9/11.

Twenty years is also a lot of time, and more and more Americans will have to be forced to remember an event that is growing less and less distinct in their minds—or that they never saw in the first place. 21.5 Americans never experienced this event because they weren’t born yet; another 21 million Americans were younger than four years old: that’s over 10% of the population.

Students who complete college next spring will be the first graduating class to have been born after the terrorist attacks, and take it from a college teacher: 9/11 is about as meaningful to them as Pearl Harbor was to me. I don’t mean to diminish either event: I recall being darkly fascinated by World War II and even thrilled by Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s words on that day, but only because living history had passed into the realm of romance and fantasy. And I worry today that any of us writing about 9/11 will increasingly be writing in the realm of romance and fantasy.

Another obvious point is that twenty years is a long time. The attacks are simply a less direct experience for anyone who was not on the spot or who did not lose a loved one on that day or from the aftereffects of the attack. Although September 11, 2001, felt deeply personal to many of us who did not lose someone or were not in New York that day, that feeling faded over time—and for most, it was only ever a mass-mediated event.

But the vast majority of us who did experience 9/11, either in person or by watching those endless loops on television, have moved on. In 2011, the tenth anniversary of the attacks, Reuters reporter Mark Egan already saw signs of this happening in New York. “Don’t call it Ground Zero, don’t use the term 9/11 widow, and don’t read the names of the dead,” some—even mayor Michael Bloomberg—told him, while survivors resisted being defined by the events of that day. Describing the area around the recently completed memorial plaza as “trendy,” Egan reported that Americans had already accepted the more dangerous and surveillance-ridden world that 9/11 made.

It seems that the promise to “never forget” might be more meaningful at the moment of a calamity than it is decades down the line when it is hard to know what, or who, we are not forgetting.

And maybe forgetting is not such a terrible thing.

Short takes:

“Because they’re mine!” Donald Trump reportedly said about the stolen government documents he refused to return. Well, you won’t be surprised that he feels that way about Save America PAC money desperately needed by languishing Republican Senate candidates. According to Rebecca Sager at The National Memo, “Trump is sitting on nearly $99 million in his PAC, and although he vocally endorses a few Senate candidates nationwide—J.D. Vance in Ohio and Blake Masters in Arizona, he has given them little more than scraps toward the financial support they desperately need.” One GOP strategist quoted anonymously in the piece said: that Trump is “a penny pincher. He’s not going to spend money on people when he can spend money on himself.” (September 12, 2022)

Numerous places across the western United States include a derogatory word used to describe a Native American woman embedded in them: Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the first Native American to head the department, wants to change that. Seventy tribal governments were involved in suggesting replacement names for 650 locations under federal jurisdiction. “The board voted Thursday to approve the replacement names, including 71 places in Idaho,” writes Clark Corbin of the Idaho Capital Sun, “as part of an effort to remove the term from federal use, according to a press release issued by the U.S. Department of Interior. Department officials said the term is an offensive ethnic, racist and sexist slur for Indigenous women.” (September 12, 2022)

Congratulations to the hard-working Heather Cox Richardson, my Substack colleague and now the spouse of the equally hard-working lobsterman and photographer Buddy Poland. The pair were married yesterday, marking the first time in Richardson’s career as a Substacker that she has taken two days off. Don’t get used to it, Heather! We need you out here in Substack-land. (September 11, 2022)

To me, this is so spot on. I was a full-grown adult on 9/11, and I know several people who lost family members on that day. But I also know someone who lost a family member at Lockerbie, and as time passes, losses near or more remote of course mount. 9/11 is not unique in my experience now as a political or personal catastrophe--it's more part of a fabric of the disappointment the 21st century, so that if I think about it it's more as part of a narrative of terror and its aftermaths (e.g., the Boston Marathon, as I live in Boston) than as a discrete event to be remembered on its anniversary. "Never forget" is an unenforceable, and perhaps lazy, exhortation. (How many people now "Remember the Maine"?) By contrast I think of efforts to help people *learn* from history (not just demand that they genuflect to it), such as the traveling exhibition "Auschwitz: Not Long Ago/Not Far Away"--efforts that take work, collaboration, and thought.

The act of remembering and forgetting is a delicate dance between the past and the present that influences the future. What is at play here applies not only to seismic national or world events, but also to the personal and private. Our careers, families, marriages, friendships all live or die by the degree to which are able to use the painful lessons learned from human interactions without throwing those same relationships in the bin. "Never forget" fossilizes events by foreclosing any space for progress. I agree with Laura Green -- the narrative should be how we learn from history rather than "demand that we genuflect to it."