Did Voters from Blue States Really Move to Florida During the Pandemic and Become Republicans?

Presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis has leveraged this assertion to bolster his claim to the 2024 GOP nomination. But it isn't true, and other Republican hopefuls need to say so.

Welcome to the weekend, friends: as we slide into August, if you are a teacher, don’t forget that episodes of the “Why Now?” podcast are a terrific addition to your syllabus. You can introduce your students to a book they won’t have the bandwidth to read for the course—or teach that book, and use the podcast to start a conversation! And as usual, if you know someone who would enjoy this newsletter, please:

One of the things that Florida Governor and 2024 presidential hopeful Ron DeSantis touts as a sign of his fitness for the American presidency is the number of people who moved to Florida during the four years he has been in charge of the Sunshine State. In May, 2021, eighteen months into the pandemic, Breitbart News reporter Amy Furr reported on DeSantis’s assertion that a pandemic-driven migration from locked-down Blue states had actually created more Republican voters. This seems to be a promise he is making to the Republican party: if you make me your nominee, I will bring in voters.

This is a potent promise for a party that seems to be able to produce robust turnout, but has been losing voters steadily, and is less and less able to compel the large independent and nonaffiliated electorate. But can DeSantis, who first became governor in 2019 and is now servicing his second term, turn it around? Probably not.

Because he didn’t do it in Florida either.

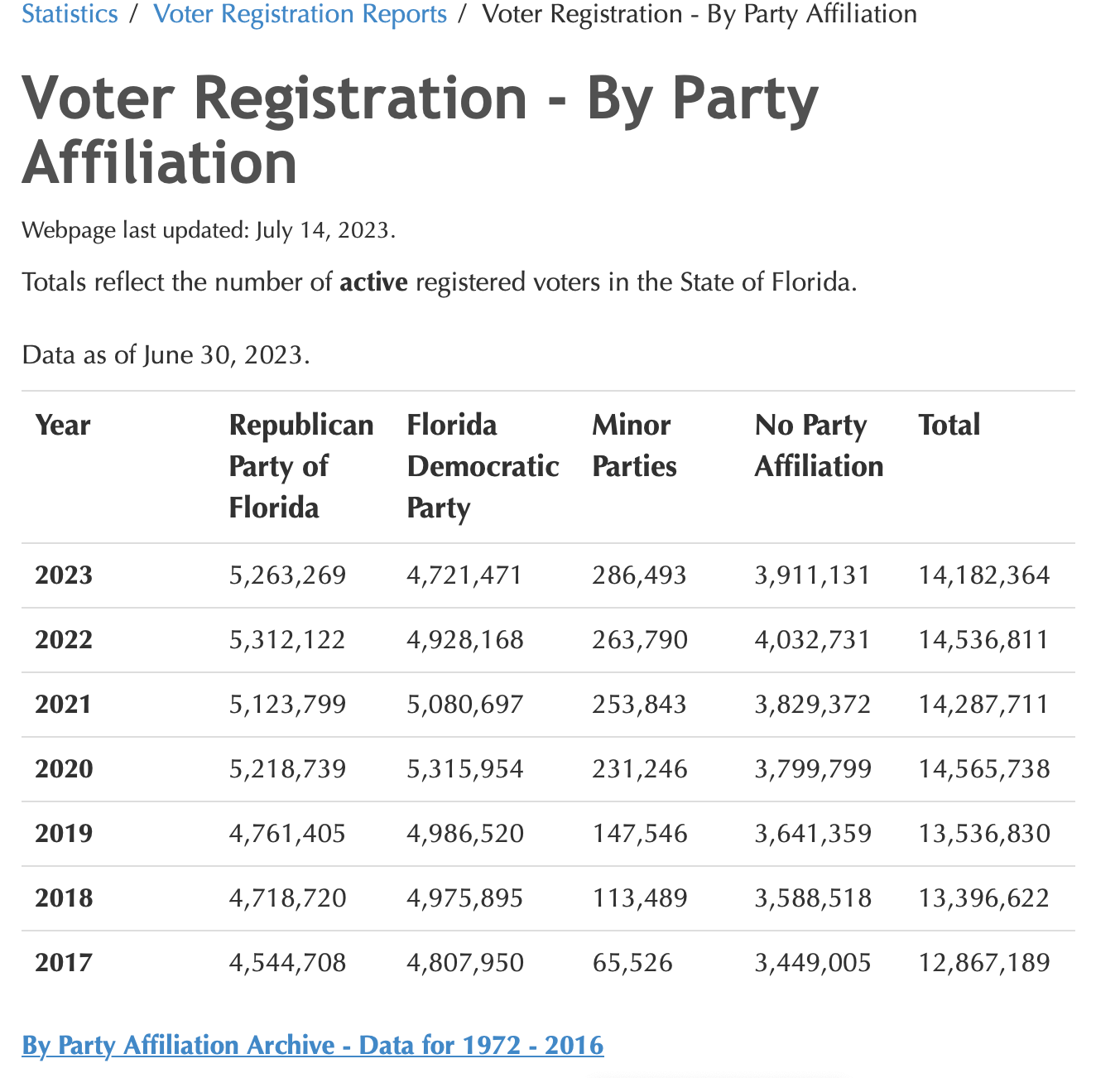

To paraphrase right-wing transphobe pundit Ben Shapiro, by attributing his pandemic policies to a resurgence of GOP voters in Florida, DeSantis was speaking about his feelings, not the facts. As you can see below, Florida was well on its way to becoming a Red State between 2019 and 2020, when Republican registrations surged to within 134,000 voters. So, the rise in registered GOP voters was mostly a pre-pandemic phenomenon (the numbers reflect registered voters on June 30) that may or may not have been related to in-state migration.

It was also a pre-DeSantis phenomenon, if you want to get picky. But the jump in Republican registrations was almost certainly related to an overall rise in registered voters during the 2020 election cycle, and Republican partisans’ anticipation that Trump would need every vote he could get. As you can see from the chart below, Florida added around 1.3 million people to the voting rolls in this period. GOP registrations did jump by 457,334 voters between June 2019 and June 2020. But registered Democrats jumped 329,434. Minor party and no party registration increased as well.

Since the 2020 election, Democratic registration has also fallen steadily, if by modest increments each year. Republican registrations have fluctuated, but the GOP now holds about a 500,000 voter advantage going into the 2024 cycle. But if you match voter registration to population growth since 2018, this is what you also see: Florida has grown by 2.5%, one point higher than the the United States as a whole, while the number of registered Republicans has grown 9.7%.

What does this mean? These new Republicans are mostly unlikely to be former Democrats from other states, as DeSantis claims, and highly likely to already existing, new, and formerly disaffected, Florida voters, a smattering of former Florida Democrats, becoming Republicans.

There is not an iota of evidence that Democrats moved to Florida and became Republicans because they loved his pandemic policies. Instead, report by Luis Noe-Bustamante at the Pew Research Center right before the 2020 election, when Florida swung decisively to Trump, argues that people who were already Trump voters moved there. Florida added 1.6 million voters between 2016 and 2020 and “in 49 of the state’s 67 counties, the increase in Republican registered voters since 2016 exceeded that of Democratic and unaffiliated registered voters.”

That said, there is another crucial piece of demographic information, according to Noe-Bustamante. In Florida counties with the greatest concentration of voters, “the biggest increase has been among those who are registered with no party affiliation. For example, in Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach and Hillsborough—counties with the four largest registered voter populations, accounting for 33% of the state’s registered voters—more people have registered with no party affiliation than as Republicans or Democrats since 2016.” In other words, during DeSantis’s two terms, Republican registrations have increased—but so has that big vulnerability that had given the GOP trouble repeatedly: independents.

And yes, Florida was one popular destination during the pandemic: there’s no doubt about that. But was it DeSantis insisting on a wide open state, policies that rank Florida third in the number of deaths from Covid-19 (California was first, and Texas second)?

Probably not. According to Business Insider’s Grace Dean in 2021, people moved to Florida during the pandemic for the same reasons they always did: the temperate climate, no state income tax, and low housing prices (which aren’t so low anymore.) And while the rise in remote work probably encouraged some to relocate, it was business migration in the financial and tech sectors that brought workers to Florida in increased numbers from cities like New York and San Francisco. But neither workers or business leaders were fleeing the “woke,” as DeSantis would tell it. They were fleeing the highest office rents and the highest housing prices in the nation.

Like Trump, Ron DeSantis has spun a fantasy about himself as a successful governor, based on demographic changes during the pandemic that he presided over, but had nothing to do with. While so far DeSantis has not pried voters away from Trump (in fact, the better Republican voters get to know him, the less they like him), it is unclear whether the former president’s candidacy for the Republican nomination will survive four separate criminal cases. So it would be unwise to count DeSantis out yet: if Trump falls apart, or cuts a deal with federal prosecutors, the Republican race is wide open.

And if that happens, DeSantis will try to ride the lies he has told about Florida to the presidency. If any other candidate in the GOP wants a shot at this nomination, they need to start asking Florida Man some hard questions now.

This week’s suggestion for fighting Donald Trump:

Give even $1 to former Texas Congressman Will Hurd (I’m giving him $5) and get him on the GOP debate stage. I can’t imagine ever voting for a Republican in the general election again, but Hurd is decent, honest, and has been anti-Trump from the get-go. He needs 40,000 individual donors to get on that stage, and there are 5,000 people on this email list. We could play a big role in getting him there.

Did you miss…

…this week’s podcast with Brooklyn College historian Barbara Winslow about the women’s liberation movement in Seattle? Listen now!

Short takes:

At The Cook Political Report with Amy Walter, Amy Walter summarizes Sarah Longwell’s research on why Ron DeSantis’s campaign is such a huge effin’ failure. In this order: he started his campaign far too late, leaving a big media vacuum for Trump to occupy by himself; instead of positioning himself as a fresh start, by running to Trump’s right, he promised more of the same (but dopier and meaner); his campaign is insular and the staff inexperienced; and the more conservative voters see of him, the less interested they are in having him replace Trump. “I am a big believer that every campaign is ultimately a reflection of the candidate,” Walter writes. “In this case, DeSantis' campaign reflected his wariness and discomfort with bringing new voices into his very small and parochial circle of loyalists — including his campaign manager, who had no experience in doing a job this big. Others in DeSantis' orbit tell me that he and his team over-read their 2022 victory.” (August 11, 2023)

Like tech giants, middle aged and older American politicians are getting physically pumped—but why? According to Matthew Rodriguez at The Nation, it’s a theme in United States history to equate healthy bodies with a healthy body politic. But even though women do it too (think: MTG and CrossFit), mostly it’s about competing masculinities. “While younger, more physically fit candidates seek to contrast themselves with Biden and Trump, Biden himself tried to embody a form of paternal masculinity, one that seeks to protect and care for a divided nation,” Rodriquez writes. “That characterization is a contrast to Trump’s blistering, bloviating masculinity, which not only downplayed physical fitness and upped the ante on mercurial aggression but also stood in contrast to the family-man persona and highly regimented exercise routine of Barack Obama.” (August 10, 2023)

When did the Claremont Institute go completely nuts? As journalist Katherine Stewart writes at The New Republic, what seemed to be a normal, conservative think tank has always leaned in that direction, and is now making a well-funded case that democracy should give way to authoritatarianism. Why should you care? “If either Trump or DeSantis becomes president in 2024, Claremont and its associates are likely to be integral to the `brain trust’ of the new administration,” Stewart, an expert on that e Christian right, warns. “Indeed, some of them are certain to become appointees in the administrative state that they wish (or so they say) to destroy.” (August 10, 2023)