On a flight from Vietnam in April 1975 were three siblings, two boys and a girl, all fathered by different African American soldiers. Their mother, Mae, rightly believed that her children would not only be discriminated against because they were racially mixed but because they were a visible sign of her own, probably necessary, collaboration with the occupiers. These children—Bear, Amy, and Peter—landed in Seattle with their belongings, where they were put on a red-eye flight to Philadelphia International Airport and from there onto a van that dropped them off at a farmhouse near Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

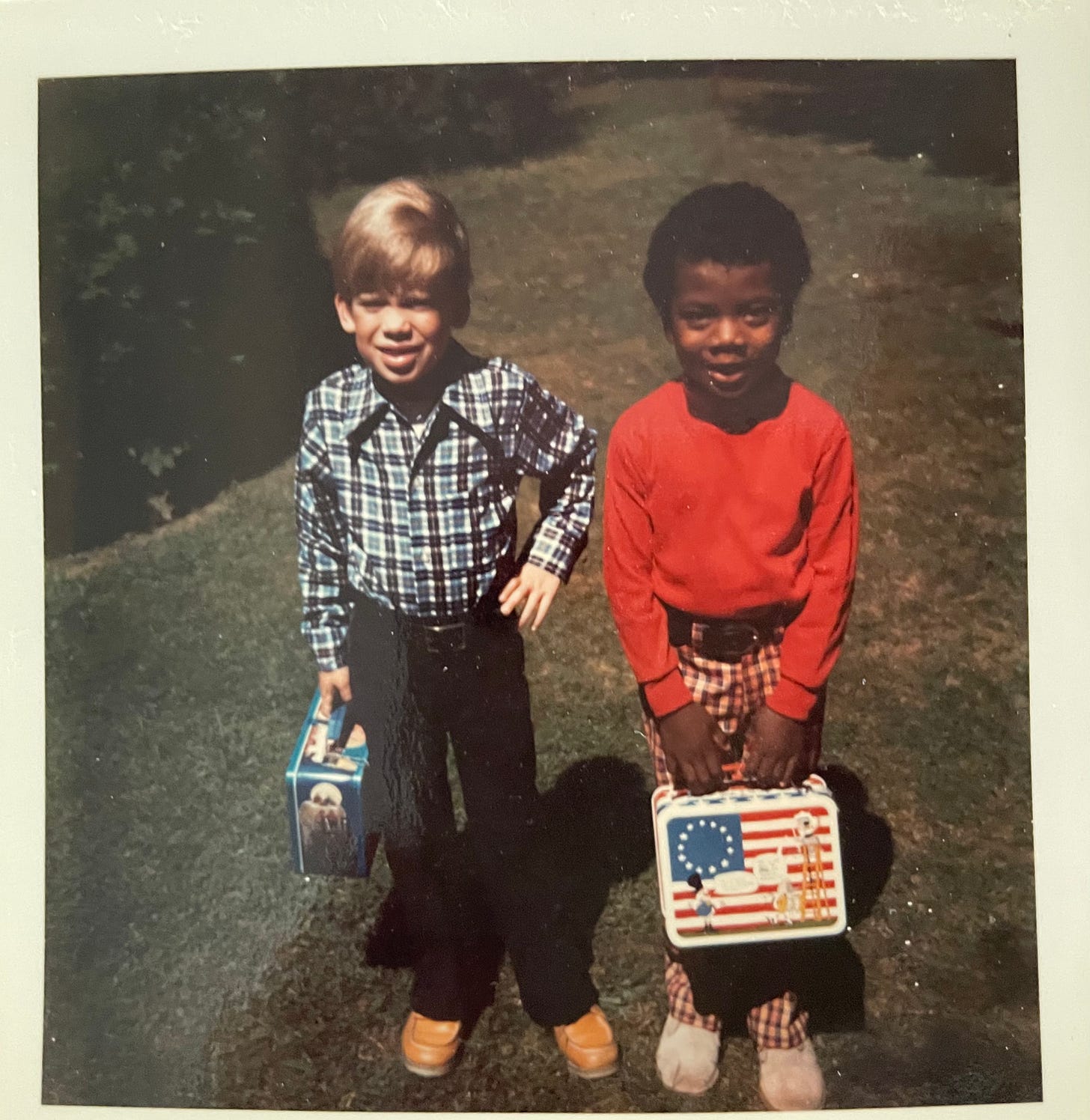

Waiting there are Bob and Sheryl Guterl, a white, Catholic, professional couple from suburban New Jersey who had watched the evacuation from afar and already contacted the adoption agency to see if there was a child for them. Bob and Sheryl had a dream, one that they had already embarked on: an interracial family that would enact their progressive principles. These commitments included anti-racism, and zero population growth. Already they have a natural son, Matthew, and his brother, Bug, who was adopted from Korea shortly after Matt was born. They know they want at least two more children. And on that April morning in 1975, Bob and Sheryl will take custody of five-year-old Bear, the same age as Matt.

Bear will be separated from his siblings—for now.

Bob and Sheryl Guterl would add three more children to the family after Bear. Sheryl will give birth to another son, Mark. Next, there will be Anna, also from Korea, whose father was a white American serviceman. And last will be Eddie, from the South Bronx, left stranded by the collapse of his community from the twin epidemics of drugs and poverty.

Bob and Sheryl would raise the family of their dreams in their white house with the white picket fence in their white New Jersey suburb. And all the while, their son Matt—known to other historians and his colleagues at Brown University as Matthew Pratt Guterl—was unconsciously starting to take notes on race and racism. Three decades later, this project would cohere after Bob’s death when Sheryl gave Matt some large, dusty boxes containing the family’s archive. The result is Skinfolk: A Family Memoir (Livewright, 2023), a beautiful and complex book about racial identity, love, and the contradictions of Bob and Sheryl’s dream, listed by the New York Times as one of the 14 books to watch in March 2023.

Program notes:

The title of this episode is from Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream Speech,” delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963. Because it is often selectively quoted by those who seek to subvert racial justice, why not take a minute and read the whole speech?

The opening sound clip is from a news report on Operation Babylift that aired on KTVU San Francisco in April 1975. For a complete account of this event, you may read Dana Sachs, The Life We Were Given: Operation Babylift, International Adoption, and the Children of War in Vietnam (Beacon Press, 2011).

To learn more about American adoptions from Korea, a set of policies now viewed critically by many of those brought to the United States as children, see Arissa H. Oh, To Save the Children of Korea: The Cold War Origins of International Adoption (Stanford University Press, 2015). Readers might also be interested in Laura Briggs, Somebody's Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transnational Adoption (University of California Press, 2015)

Matthew Pratt Guterl references the carceral state and the “school to prison pipeline.” To learn more about these ideas, in which people of color are directed towards incarceration by structural racism, read Emma Shaw Crane’s article, “The New Geography of the Carceral State,” Public Books (September 21, 2022) and a University of Michigan research initiative, “What Is the Carceral State?” (May 2020).

Explaining his parent’s political ideals, Guterl mentions Hakim Bey’s theory of immediatism. You can purchase Bey’s book, Immediatism (AK Press, 2001), or you can read an open-source edition at The Anarchist Library.

Guterl also mentions the abolitionist John Brown. You can watch a PBS documentary on Brown here or read W.E.B. DuBois’s classic 1909 biography of Brown. The most recent biography of this activist is by Stephen B. Oates, To Purge This Land with Blood (Echo Point, 2021).

To learn more about the “white gaze,” see George Yancey’s Black Bodies and White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race in America (Rowman and Littlefield, 2008). For an example of the “white gaze” in action, see Ian Frazier’s article in The New Yorker (August 19, 2019) about the display of Black bodies and a public debate between DuBois and white supremacist Lothrop Stoddard.

Guterl references the epigraph of David Levering Lewis’s pathbreaking book about Black cultural history When Harlem Was in Vogue (Penguin Books, 1997; originally published in 1979).

You can download this podcast here or subscribe for free on Apple iTunes, Spotify, Google Podcasts, or Soundcloud. Do you use another service? Let me know in the comments, and I will submit it to them!

Share this post