Where Did You Put My Office?

How WeWork, a failed co-working startup that tried to upend workplace culture with ping-pong, beer, and a huge dose of woo-woo, has been reborn for the post-pandemic workscape

Today’s post is free to all subscribers: please forward it to an interested friend who might join us.

Photo credit: Noam Galai for TechCrunch/Wikimedia Commons

As far as WeWork is concerned, we're not competing with co-working spaces; we're not competing with office suites. We're competing with work. We think there's a new way of working in the world, and it's just better. For the millenials and everybody that understands collaboration and the sharing economy, that's just the right way for them.

Adam Neumann, former CEO of the We Company

What is the “best way of working?” Workplace designers have struggled with this question for over a century, and it produced such dystopian innovations as the sweatshop, the assembly line, and the cubicle. In the 21st century, fueled by the apparent success of tech companies where workers played, ate, and brainstormed as they slouched in bean bag chairs, it produced the co-working space, and open-plan “hot seat” spaces where employees swaddled in headphones stayed focused on their own screens in between meetings and skull sessions.

Over time, companies have successfully moved all, or part, of their workers into private spaces. In the late nineteenth century, that meant turning gloves and rolling cigars in a tenement on the Lower East Side of New York, and by the late twentieth century, connecting to a call center from or running a knitting loom in your own home.

Since March 2020, while working-class people have kept society going by working in person, most professional workers have been shut out of their offices. They have cordoned off a section of their homes as telecommuting spaces. If you have been to the ghost ship they call Midtown Manhattan recently, it is clear that something seismic is occurring, not just in commercial real estate, but in what the American corporate workplace of the future will look like. A year after shifting employees out of offices and into their homes, it’s clear that—however uneven the experience for workers themselves—significant sectors of the corporate economy can function more cheaply, with a majority remote workforce.

Cities will change, as one reporter recently inferred, down to the level of the hotdog vendor.

For the first time since the 1970s, when corporations moved to the suburbs where their workers had migrated before them, the changes wrought by the pandemic now pit the economic interests of big employers against those of real estate developers. As importantly, the shift of work into our homes, viewed as temporary in the spring of 2020, will be an opportunity to realign those interests.

It is not unreasonable to see the redesign of work in the coming years as a version of what Naomi Klein called, in a 2007 book, “shock doctrine.” Shock doctrine dictates that a crisis substantial enough to disorient, distract and preoccupy large numbers of citizens will render them unable to resist, or even comprehend, major shifts in economic life that will—in the name of freeing individuals—further disadvantage a professional middle class that is already wheezing under the strain of modern life.

The pandemic is obviously just such a crisis. Given what it costs to rent commercial space in Manhattan and other major cities, who is surprised that corporations (and probably some universities) will leverage a human catastrophe into big savings? McKinsey & Company, a consulting firm that can help you run anything from a war to a university in a thriftier way, believes that downsizing the office will be a worldwide phenomenon in the post-pandemic workscape. Between “20 to 25 percent of the workforces in advanced economies,” one McKinsey report estimates, “could work from home between three and five days a week.” This isn’t just wishful thinking. Corporate executives surveyed in August 2020, less than five months after the pandemic struck, projected that they would shrink office space by 30%, with 25% of white-collar employees working from home three to five days a week.

The private office era, and even the homey cubicle decorated with family photos, plants, and tchotchkes, could be over—because really, what is homier than your actual home? Expect to see glowing style pieces about how fulfilled women are when they can do a full day’s work and still greet their children at the school bus every day. Expect a not-too-distant study about how sexual harassment claims have dropped precipitously, now that no one can touch each other anymore.

Your willingness to work from home will also subsidize corporate profits. There won’t be any reason not to come to the office when you or someone in your family is ill. Without commuting, work can begin earlier and end later. Much as Uber figured out that they could run a transportation business without buying vehicles, and AirBNB’s virtual hotel required no investment in real estate or staff, anyone who wants a job should be prepared to subsidize their own work by paying for rent or a mortgage, telephone, internet, utilities, and office supplies.

But not to worry: on the days you do come in, there will be a long, white table, a coffee pot, and ping-pong waiting for you, a place where most of the employees that make up the other 60% work while you stay home making sack lunches with one hand and doing email with the other. Human Resources departments will encourage us to see these developments not as a loss of community or privacy but as a triumph of flexibility, freedom, collaboration, and individual choice. This vision will be tarted up with theories about how much more innovative and creative we are when we work collaboratively, online or onsite.

So who is surprised that at this moment, one of the epic business fails of all time, the co-working startup WeWork founded by eccentric Israeli entrepreneur Adam Neumann, is back? WeWork, you may recall, had a simple business model: lease raw space, and convert it into co-working units supplied with beer, games, snacks, and comfy furniture from Ikea. Following a failed initial public offering in the fall of 2019 and dogged by massive losses, WeWork was then buried by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Recently purchased for $9 billion by Bow X (a special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC), WeWork will soon reopen its doors to public investment under Bow X’s NASDAQ listing. And our current crisis may produce, not just a revival of coworking, but an urgent need for what WeWork failed to provide in its earlier incarnation: experts to administer slimmed-down white-collar workplaces.

Co-working spaces are essentially hotels for businesses. Although Neumann tried to shill WeWork as a technology startup, it was always just a poorly run real estate company. Neumann leased lofts, floors of skyscrapers, sometimes whole buildings. He also profited from purchasing buildings that he then leased back to WeWork. Neumann chopped up these spaces into open-plan offices designed to look like (and appeal to) digital entrepreneurs.

It could have worked. Any small business, and even large corporations that suddenly needed more space, could benefit from flexible leases that allowed them to move on when they wanted or needed to. And it wasn’t just corporations that saw this. Several years ago, as it prepared to renovate its townhouse in Washington, DC, the American Historical Association moved into a WeWork on a short-term lease.

The problem was that Neumann, who had previously created a modestly successful baby clothes company, had loads of charisma but no real estate experience. He also had no business plan aside from endless platitudes about creating community, aggressively stealing other people’s tenants with reduced or free rent, acquiring competitors, and sucking up round after round of funding from billionaires that paid him to lose money.

Someone should have stopped him. But in 2010—as the nation was still rebounding from recession, office leases were dipping in price, and job seekers in suits packed coffee shops—it also seemed reasonable that co-working spaces would anchor the 21st-century economy. The signs were encouraging. By 2014, WeWork was leasing more space faster than any other company in New York and extending its vision to the rest of the nation—and the world. But other signs spelled trouble. Neumann spent lavishly on himself and encouraged other executives to do so too; he acquired other companies on a hunch; missed meetings; seemed to smoke a lot of dope in the office; and invested in projects for which there was no apparent need.

Why was anyone fooled by Neumann’s pitch, when it was obvious that he was out of touch and out of control? For the same reason that Ronald Reagan believed in the Laffer curve: voodoo economics. Neumann embraced a theory of profitability popular among venture capitalists in the 2010s called “blitzscaling.” A technique by which tech companies successfully dominated a particular market for goods or services (think Amazon, Facebook, Zipcar), blitzscalers grew a company at lightning speed, acquired any and all competitors, and presumed that outsized losses for an indefinite period would ultimately result in a massive payday down the line.

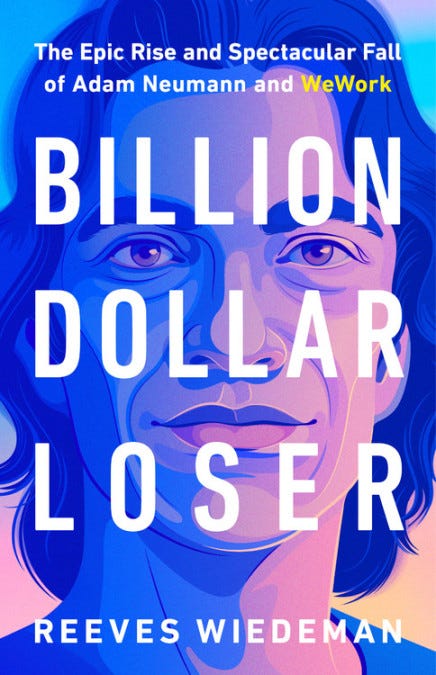

Except that, while that payday came for Neumann, it never arrived for WeWork. You can read the whole horrifying story in Reeves Wiedeman’s Billion Dollar Loser: The Epic Rise and Spectacular Fall of Adam Neumann and WeWork (Little, Brown, 2020), a business history that reads like a novel. (I recommend that you pair it with Dave Eggers’s 2014 novel, The Circle, which—dystopian though it may have been—may have informed Neumann’s vision for a cradle-to-grave community delivered by a single company.)

Wiedeman is a contributing editor at New York Magazine and began working on the story about a year before WeWork’s IPO was supposed to launch. You might say he came to document what was widely perceived as a triumph of corporate disruption and he stayed for the implosion. As WeWork moved closer to its debut as a publicly-traded company, the wheels came off a company plagued by nepotism, greed, fuzzy-minded thinking, and staggering unprofitability.

Why did WeWork fail to launch in 2019? One reason is that Neumann, a highly narcissistic leader given to rambling, inspirational speeches fueled by group tequila shots, burned recklessly through billions in venture capital between 2010 and 2019. Vast sums ended up in Neumann and his wife Rebekah’s own pockets as they purchased one multi-million dollar home after another and sunk company cash into subsidiary businesses that amplified their personal brand without contributing anything to corporate profitability.

This collection of fanciful projects imagined Americans spending their entire lives enmeshed in what was renamed the We Company. Participants would become creators in WeWork offices, where an internal network linked them to potential collaborators and vendors. They would belong to fitness centers called Rise by We. They would occupy co-living spaces called WeLive. Children would attend WeGrow schools (otherwise known as SOLFOL, an acronym pronounced “soulful” that stood for “school of life for life,” whatever that means.) Future workers would be global citizens, with everything they need to sustain a life wherever they landed, for however long they needed it.

A 2018 article in the New York Times dubbed this vision for transforming American work culture through the kibbutzim ethic Neumann had grown up in “brash” and “ambitious.” But WeWork and its sister enterprises were a money pit, animated by a level of woo-woo thinking rarely seen outside of a New Age intentional community. Coddling Neumann as a genius and a visionary, in part, I suspect because he echoed their own ideas back to them in his own language, SoftBank and other investors finally ran out of patience and cash in 2018 and insisted that the company go public.

Predictably, because he had little idea what he was doing, Neumann ran into a wall. After a frantic summer, the team preparing for the IPO finally issued a sloppy and incoherent S-1 filing, the internal report that shows the Security and Exchange Commission that a business has a route to profitability and the value it says it does, in September 2019.

The filing demonstrated that WeWork was just as badly run as many suspected it was. Potential investors ran for the hills, and the company’s value dropped by 80%. In the ensuing collapse of the IPO, Neumann was ignominiously hustled out of his own company. But he was also now a billionaire, having extracted so much money from the company along the way.

Having already covered Travis Kalanick’s 2017 crash and burn at Uber, Wiedeman had some idea what he was looking at and why it happened. Until far too late in the game, investors such as SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son and tech VC Benchmark perceived Neumann as a unique and charismatic genius. Instead, Wiedemann saw a troubled and erratic narcissist who missed meetings to go surfing, lived in luxury while promises to employees went unfulfilled. WeWorkers openly spoke of the company’s culture, not as the workplace of the future, but as a cult.

Yet WeWork still exists. So do many of the leases Neumann acquired on space owned by real estate corporations whose portfolios are hemorrhaging value. These leases are ripe for renegotiation. Imagine frantic real estate executives with arms full of canceled leases ready to sign sweetheart deals with anyone.

And imagine the equally frantic businesses trying to return to profitability in the post-pandemic world by shrinking their office footprints, shedding everything from office managers to cleaning services. And imagine a WeWork reborn, not as a fantasy about community and inspirational work culture, but as a wrap-around provider of office space at a low, low price.

You should try to imagine it—because it could be your destiny.

Claire Bond Potter is Professor of Historical Studies at The New School for Social Research and co-Executive Editor of Public Seminar. Her most recent book is Political Junkies: From Talk Radio to Twitter, How Alternative Media Hooked Us on Politics and Broke Our Democracy (Basic Books, 2020).

What you missed:

In this newly-opened post from last Friday’s newsletter, I explore the question of who funds Trump whisperer Steve Bannon’s internet broadcasts. (Hint: you probably do business with more than one of these companies.)

What I’m reading:

It’s a Godzilla versus King Kong thing! But with Rupert Murdoch! Dominion Voting Systems and Smartmatic are already suing some of the people around Trump who lied about their machines malfunctioning on November 6, 2020. They are now going after Fox News for spreading the lie, and they want serious damages. (Kerry Eleveld, The Daily Kos, March 26, 2021)

And taking the fight against disinformation to broadcasting is exactly the right thing to do. (Nicholas A. Ashford, New York Times, March 29, 2021)

But it isn’t just broadcasting. The Astro-Turfy “Stop the Steal” Movement was financed with corporate dollars contributed by Mike Lindell of MyPillow.com and Publix supermarkets heiress Julie Jenkins Fancelli. (Soo Rin Kim, ABC News, February 24, 2021)