We begin this episode with a June, 2021 school board meeting in Loudoun County, Virginia, where a mob of angry white parents had taken over the room. They demanded that the district stop using tax dollars to make curricular and structural interventions about race and racism. They also raised the flag of “parents’ rights,” a pandemic-born political call to arms that insisted on their right as parents to make decisions about what their children learned about the nation’s racial past and present.

Along with the rest of the state, Loudoun County had mounted massive resistance to desegregation in the 1960s, closing its schools rather than mix Black and white students. But the school district had traveled a long way from its own racist past. Responding to the county's demographic transformation from a white, rural enclave to a diverse, tech-oriented suburb of Washington, D.C., Loudoun had introduced an equity plan in 2019 that promised better inclusion for students of color. In the words of NPR reporter Colleen Grablick, the plan consisted of "implicit bias training, enhanced protocols for handling racist behavior, and improved reporting systems for students."

Subsequently, five parents sued the school board, launching a new political struggle that put the teaching of race, as well as education about gender and sexuality, in the national spotlight. While that lawsuit, and a second one, were dismissed, the parents' group, Fight for Schools and Families, continued to harass the school board and pursue recall campaigns against its members.

But Fight for Schools and Families wasn't the grassroots group it claimed to be: it was a political SuperPac, formed on June 1, 2021, just before the Loudoun County action. The bulk of its spending went to midterm attack ads against Democratic House candidates Jennifer Wexton and Abigail Spanberger, who were running for the House in Virginia's 10th Congressional district, which makes up much of Loudoun County, and the neighboring 7th. While those attack ads took up another theme—false charges that activists wanted to jail school officials who failed to address students by their chosen pronouns on felony charges—in 2021, it was also clear that the attack on Loudoun’s schools was intended to boost the candidacy of Republican Glenn Youngkin for governor.

Did it work? You tell me. Wexton and Spanberger won—but so did Glenn Youngkin, even though he lost Loudoun County. Democratic challenger Terry McAuliffe only won this blue county by 55%, a reduced margin from Biden's 61% in 2020. It was a key factor in a narrow loss.

Curriculum controversies are not just abstractly political. The strategists that run campaigns believe that they have the potential to turn blue districts purple, and purple districts—whole purple states—bright red. Predictably, since Youngkin’s victory, arguments about teaching race in school have only become more heated and riddled with disinformation disseminated by right-wing extremist groups like Moms for Liberty, the 1776 Project, and the Ron DeSantis-led Republican state government of Florida.

But these attacks are also riddled with tales of woe illustrating the harm that white true believers conjure from Black history and literature. At the contentious Loudoun hearings, white parents reported that their children, and even teens, were traumatized by encountering the United States' racial past in fiction and history texts. And after the election, Republicans repaid this small group of voters for their efforts, stripping Virginia’s curriculum of many of the subjects and interpretations they had protested.

Suppose you are a dedicated reader of this podcast's companion Substack, Political Junkie. In that case, you know that versions of this story—a broad-based Republican campaign to win a permanent governing majority under the false flag of an AstroTurf "parents' rights movement" is playing out nationwide.

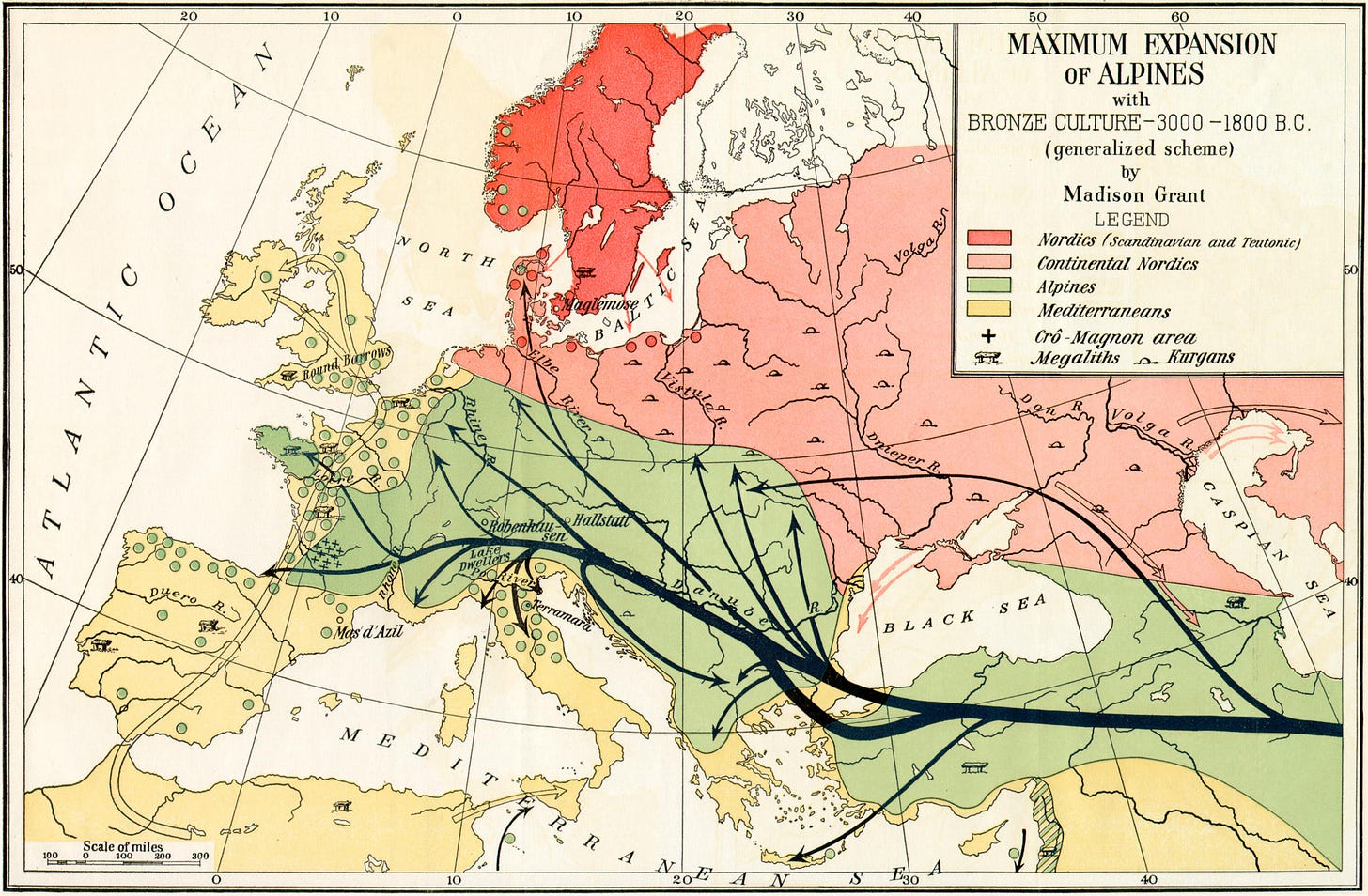

Furthermore, these inquiries cut to the heart of the alternative past that the right cherishes but refuses to name: that the history of so-called Western Civilization is the property of European-descended people. In other words, if we are to understand the revived vitriol towards Blackness, we might want to start by re-examining the murky past of American whiteness.

So, I returned to historian and visual artist Nell Irvin Painter's 2010 book, The History of White People (W.W. Norton, 2010). Painter, one of this country's pre-eminent historians of the nineteenth century, race and the African American past, traces the history of this fictional white race from antiquity to the present. She began her research with a simple question: why, for several hundred years, had white people in the United States called themselves Caucasian—when the Caucuses, an Eastern European region bordering on Asia, were a place where most white people's ancestors did not originate?

Program notes:

The full Reuters feature on the June, 2021, Loudoun County school board meeting is posted here.

Nell references the early German anthropologist and race scientist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752-1840): you can read a profile of Blumenbach here.

Nell mentions artist’s books where she also worked on the problem of whiteness: you can see that, and her other work, on her website.

Claire mentions the Tea Party’s reaction to the election of Barack Obama, and the re-orientation of racism on the right at that moment. One resource for that is Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williams, The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism (Oxford, 2016.)

Listeners who are interested in whiteness studies may wish to do more reading: sociologists Cara Cancelmo and Jennifer C. Mueller are the authors of a 2019 Oxford bibliographical essay; Matthew Wills has written an accessible historical essay at JSTOR Daily (September 12, 2016.)

Claire namecheck’s Linda Colley’s Captives: Britain, Empire, and the World, 1600-1850 (Pantheon, 2003.)

Nell points to the importance of Orlando Patterson’s work on slavery: listeners may wish to begin with Patterson’s classic text, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative History (Harvard, 1982.)

Nell also references an organization that is fighting the new censorship, Freedom to Learn.

Nell references a 2015 article she wrote in the New York Times that white people might want to call themselves abolitionists, to tap into a long historical tradition of white antiracism: you can read it here.

You can explore the antiracist group John Brown Lives! by navigating to the group’s website.

Nell points to a growing literature on how to be an antiracist: readers may wish to start with Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (One World, 2019.)

You can listen to this podcast by downloading from this newsletter, or you can subscribe for free on Apple iTunes, Spotify, or Soundcloud.

If you enjoyed this episode, try:

Episode 22, Hit Them In The Pocketbook: A conversation with Annelise Orleck about her book, "Storming Caesars Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty."

Episode 16, The Sunlit Path of Racial Justice: A conversation with historian Matthew Pratt Guterl about his new book, "Skinfolk: A Memoir."

Episode 3, Black and White Together: In this episode of "Why Now?" historian Victoria Wolcott discusses prefigurative politics and her book, "Living in the Future: Utopianism and the Long Civil Rights Movement."

Episode 2, The First Family of Abolition: A conversation with historian Kerri Greenidge about her new book, "The Grimkés: The Legacy of Slavery in an American Family"

Share this post